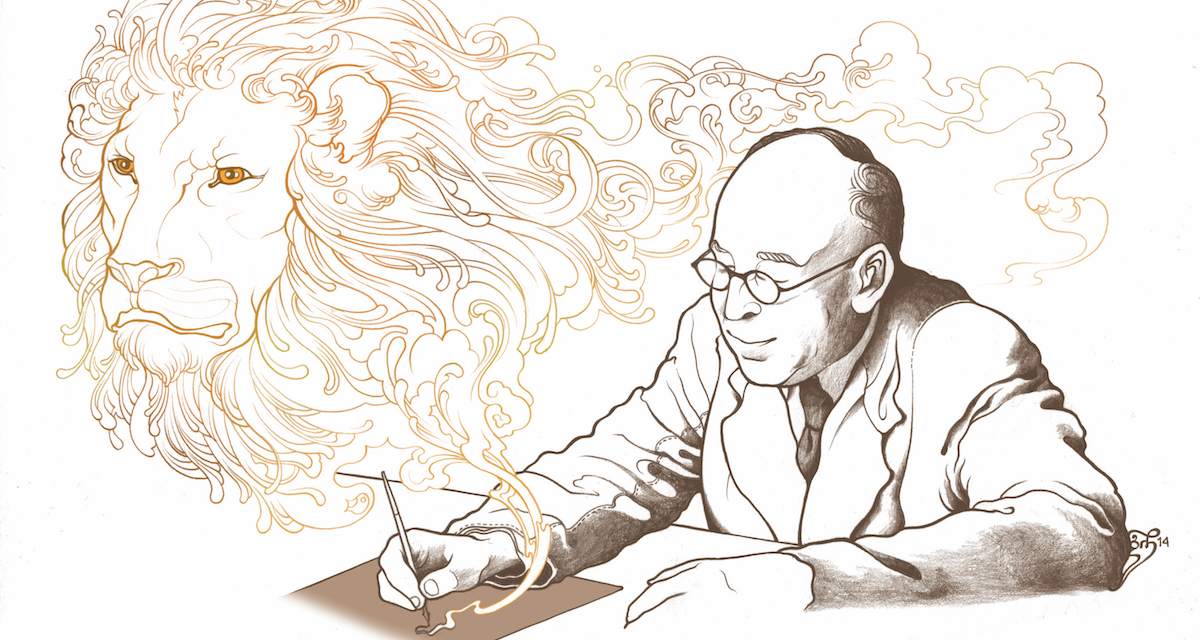

5 Ways We Can Be More Like C.S. Lewis on His Birthday

A year ago, Netflix bought the rights to C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia (for nine figures), and last summer they hired Matthew Aldrich, one of the writers for Pixar’s Oscar-winning movie Coco, to oversee the creation of several film adaptations and quite possibly a miniseries. Although the release date is still a mystery at this point, it goes to show that C.S. Lewis and his stories are still important to us.

In celebration of Lewis’ birthday today, The Bell interviewed Inklings scholar, Ph.D. student and English professor Sørina (Kulberg) Higgins ’02, who has spent the last 17 years studying the works of writers Charles Williams and C.S. Lewis. From her interview, The Bell identified five ways that we can be a little more like Lewis in the 21st century.

Here they are:

Befriend Those You Don’t Agree With

For much of his life, C.S. Lewis was not a fan of T.S. Eliot or his poetry, and he was very vocal about it (he went as far as to liken Eliot’s poetry to poison in A Preface to Paradise Lost). Though the two Anglican writers weren’t the most amiable of dinner companions, they eventually reconciled. Higgins explains, “Charles Williams was best friends with both of them. When Williams died young and unexpectedly in 1945, that brought them together. Late in life, they worked on a revision of the Psalter”. They didn’t come to an agreement about the conventions and style of modern poetry (their biggest sticking point), but that didn’t stop them from becoming friends.

Have the Humility to See When You’re Wrong, and Change Your Mind

It probably comes as no surprise that Lewis loved debates. When he was on the faculty at Oxford, he was the president of a Socratic dialogue club. On one occasion, Lewis faced Elizabeth Anscombe, who would later be regarded as one of the most gifted philosophers of the 20th century, and he lost. “She beat him in the debate,” says Higgins. “She points out that his argument for the existence of God is a bad one.” Instead of sulking or defending himself, he rewrote his argument (a whole chapter of his book Miracles). Higgins points out:, “It’s such a good model of civil discourse—of rethinking our positions after listening to another person.”

Choose Hope Instead of Hopelessness

Lewis fought in World War I and lived through World War II. Like so many in Britain at that time, he suffered from great loss and what we would now call PTSD. Many writers, like T.S. Eliot and Wilfred Owens, chose to capture postwar feelings of disenchantment and hopelessness in their work, says Higgins, but Lewis and the Inklings sought enchantment through myths and Arthurian legends. In the years following WWII, as many writers continued to lose hope in the world (and in general), Lewis put his hope in the world to come—a hope that is at the heart of his work from that point onward.

Practice Intellectual Hospitality

All of Inklings practiced something Diana Glyer, another Inklings scholar, called intellectual hospitality—treating ideas the same way we treat our guests. “You invite ideas into your mind the way you invite people into your home,” says Higgins. “They don’t have to live with you for the rest of your life, but you do have to be friendly and gracious to them and listen to them while they’re visiting. At the end, you can show them the door or you can marry them.” Even though Lewis didn’t like Eliot’s poetry, he still read it.

Desire to be Changed and Humbled

When you read many of Lewis’ works, as Higgins has done, you notice that Lewis changes a lot over the course of his life. It’s something that’s often overlooked, says Higgins. Many fans of C.S. Lewis focus on the change in him that came with his conversion to Christianity, but don’t take notice of how much he grew after he married and later lost his wife. In his youth, Lewis was a bit cocky, explains Higgins. As a young man, he believed his arguments were obvious and irrefutable. But after he married Joy Davidman—an American writer and poet who, in Higgins’ words, was “razor sharp” and the kind of woman “who takes no nonsense”—his writing style and perspective changed. “After his marriage, his views of women became much more thoughtful. Till We Have Faces is written from the perspective of a woman, and it’s a much more thoughtful, psychological work. It really changed him. It made him less glib.” Of all the works we could read or reread in 2020, Till We Have Faces, A Grief Observed and Letters to Malcolm are, in Higgins’ mind, the ones we should return to most because they offer Lewis to us at his humblest.

For more writings about C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams and the other Inklings, visit Higgins’ website, read her newest book or take one of her online classes at Signum University.

The Bell

The Bell