Biology Major Researches Kidney Transplants at Duke University Lab

This summer, Verna Curfman ’17 (biology) joined forces with renowned scientist and transplant surgeon Dr. Stuart Knechtle of Duke University School of Medicine to understand why the human body sometimes rejects transplanted organs, despite desperately needing them.

This summer, Verna Curfman ’17 (biology) joined forces with renowned scientist and transplant surgeon Dr. Stuart Knechtle of Duke University School of Medicine to understand why the human body sometimes rejects transplanted organs, despite desperately needing them.

What scientists do know is that the unfortunate phenomenon happens during the process of sensitization, which occurs when the body is exposed to cells from another person. Essentially, exposure to foreign cells from an organ transplant can cause the immune system in some patients to create defense line of antibodies to fight off the new cells from the donor. But the problem is that the patient needs those new cells to survive. Ultimately, if the patient has these antibodies the body begins to reject the new organ—which leads to complications and possible death.

For sensitized patients, transplants aren’t impossible—but the waiting time for a compatible donor is significantly elongated.

Curfman and Knechtle searched for drugs that could decrease the type of cells that create the antibodies, which would reduce the likelihood of the body rejecting the organ. In an attempt to find the most effective drug, they measured the impact of various drugs on live monkeys that had received kidney transplants. Each test involved administering a different drug to the monkeys, and then collecting and testing cells to determine their composition.

By identifying the types of cells mediating the immune system, scientists at the lab can then observe how those cells respond to different drugs and what impact those drugs have on the overall health of the transplanted organ and the monkey. When the right reaction of medication is discovered, the lab hopes to send the drugs on to human trial. “We hope that these medications can help make transplants more accessible to a larger number of people,” Curfman said.

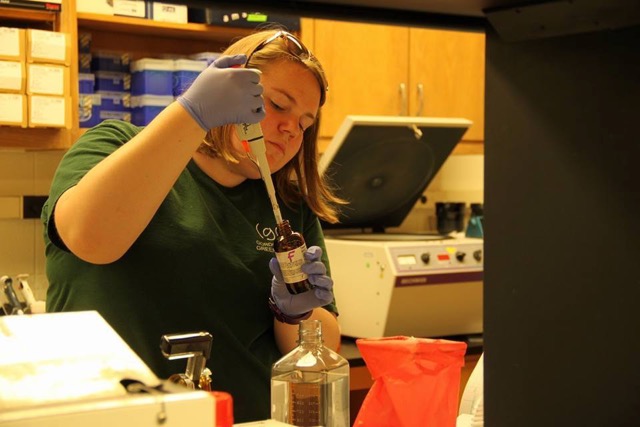

As an intern, Curfman’s job was to process blood samples, identify cells and analyze data. She also tracked the monkeys periodically for any change in antibody production. But it wasn’t all grunt work. She had the unique opportunity to network with top surgeons—including the chief of surgery at Duke—by attending meetings and sitting in on brainstorm sessions. Seeing their passion for finding cures, she says, was one of the more inspiring aspects of her internship.

“These studies have the potential to help a lot of people,” Curfman said. “I got to work with such hardworking and dedicated people who ask new questions and are ready to put in the long hours. I was very happy to be here!”

By Alex Rivera ’16, English language and literature

The Bell

The Bell