Can GMOs Honor God? Dr. Ming Zheng’s Research in Biotechnology

What if you could grow the perfect corn—every time you planted a seed, it would always produce the most yellow, juicy, healthy ear you’ve ever seen? Farmers and scientists have been trying to breed the best-quality crops for centuries, but weeding out bad qualities and keeping the best ones is a process that has often taken multiple generations of planting and years of hard work.

In more recent years, and thanks to the work of plant geneticists like Dr. Ming Zheng, professor of biology, this process can now take a single generation. Zheng spent his recent sabbatical in research labs exploring how to make immature corn pollen systems reproduce more quickly—which will ultimately help people get the food they need faster.

A New Kind of Plant Engineering

Traditionally, genetically engineering crops involves breeding different plant varieties and crossing the variations. With each new generation of planting, scientists segregate the plants that presented the desired trait—if they were lucky enough to grow any—and continue growing these until they achieved genetic stability, meaning all the crops were growing exactly alike with the desired trait. While that method still works, it is highly inefficient, often taking five to seven years and 10-12 generations to achieve homozygosity—perfect expression of the desired trait.

Having grown up in Mainland China, Zheng saw firsthand how difficult it can be to breed crops into new cultivars (cultivated plants with a specific, desirable trait combination) in a manageable timeframe. With the rise of climate change, farmers need to develop crops that are resistant to extreme temperatures and environmental stressors faster than ever.

“It’s a global issue; I would love to find a way to help plant breeders develop new cultivars more rapidly,” Zheng said. “Double haploid technology (achieving instant homozygosity or genetic purity in one generation) can help us do that.”

How is Corn Scientifically Engineered?

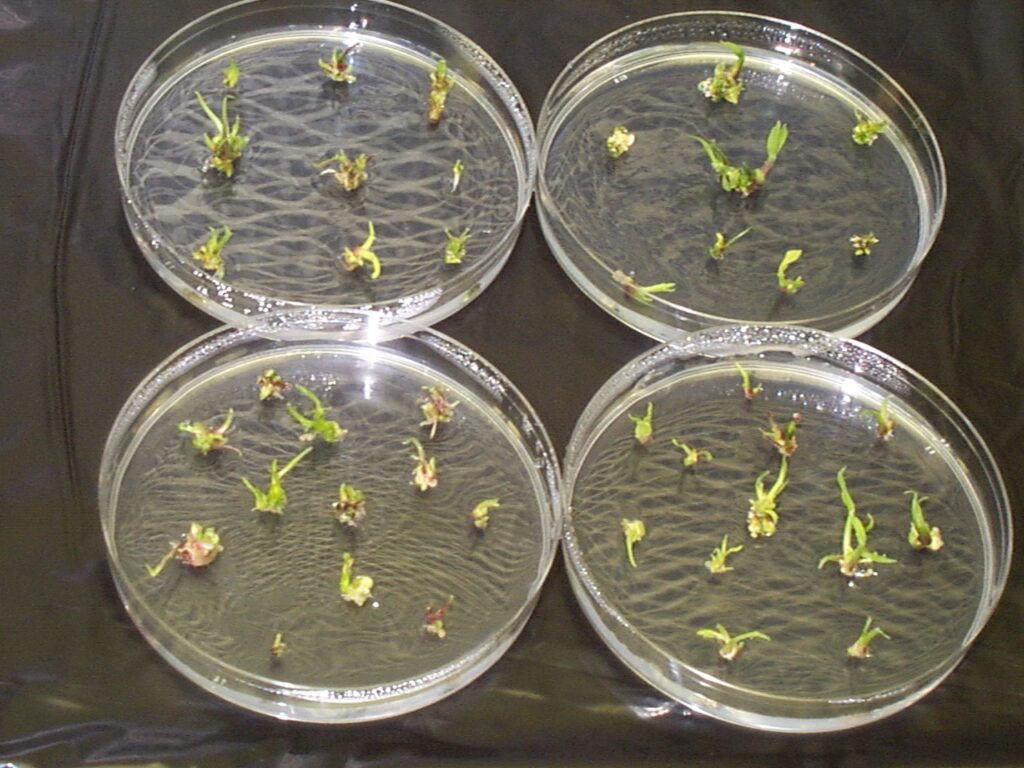

Every plant has male and female organs, and one male organ (an anther) contains a few thousand microspores, or immature pollen cells. As the plant grows these microspores divide and develop into 2,000-3,000 mature pollen cells. But if you put stress on the cells, such as starvation or chilling temperatures, they backtrack in their development to an embryonic state where their development program can be altered.

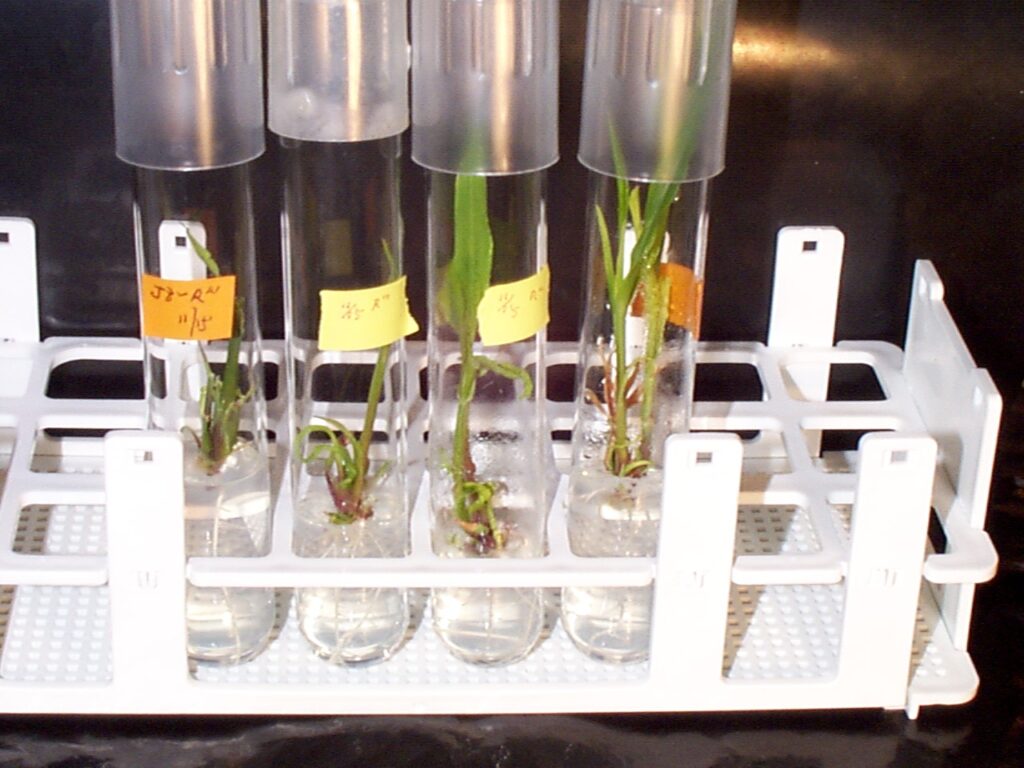

For his research Zheng grew corn in the Gordon greenhouse until the crops were at the right maturity for the experiment. “In humans we have half of our DNA from mom and dad each; it’s the same for corn,” Zheng explained. “But in this embryonic state, there’s a spontaneous doubling of the chromosomes without dividing the first time. Then from the second division onward, they divide normally, so they have a pair of the same set of chromosomes—these are what we call ‘doubled haploids.’ Haploid cells only have one set of the chromosomes; doubled haploid cells have two identical sets and thus achieve perfect genetic homozygosity in one generation.”

Zheng’s sabbatical was dedicated to finding the right stressors and parameters to ensure the corn plants’ cells would be properly reprogrammed, dividing and developing into pseudo-seeds that would produce the desired traits every time. The key to the research’s success was efficiently reprogramming immature pollen cells, using the optimal combination of plant hormones and medium ingredients.

“We found a carbon source, a type of sugar, to feed the cells after we reprogram them; it makes a difference in how many pseudo-seeds you get. In addition, the proper combination of plant hormones, or plant growth regulators, used in culture is crucial for a high yield of doubled haploids,” he said.

The Cross Section of Science and Faith

Having worked in plant biotechnology and crop breeding since his graduate studies, the concept of biogenerated food holds no tension for Zheng or his Christian faith. “Humans have been genetically modifying crops for thousands of years; the tools are just different now, with the use of cross-breeding and gene splicing. One of the advantages of genetic engineering is that we can change individual genes without changing the whole genetic makeup of plants. GMOs, when done right, can make food healthier. For example, insect-resistant plants reduce the amount of pesticides used, which makes food cleaner.”

Zheng plans to continue his research beyond his sabbatical with the aid of several Gordon biology students, as the demand for good food produced quickly will only continue to grow in our ever-expanding human population. “I’ve been training [my research students] on how to make cell cultures, use fluorescent microscopes and track cell division and development using inverted microscopes. Once they graduate, go to graduate school or enter industry, they will be well-prepared to use these skills to be successful and serve the Lord in whatever capacity they seek.”

The Bell

The Bell