For Modern Democracies to Survive, We Must Rally Behind Universal Human Dignity

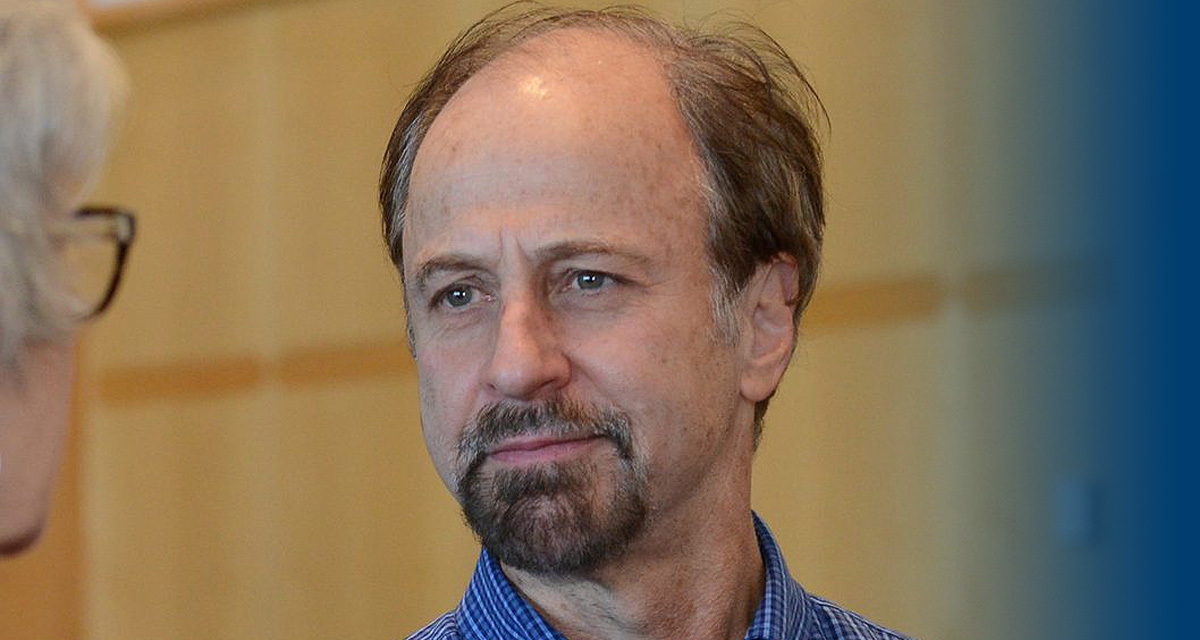

Just over a year ago, the French Senate passed a measure that would ban any girl under the age of 18 from wearing a hijab in public. Although it’s unlikely to become an official law in France, it illustrates how Christian-majority democracies often fall into the trap of not extending religious freedoms to people of other faiths, says Dr. Robert Hefner, professor of anthropology and global affairs at Boston University. Yesterday as part of the 28th annual Franz Lecture titled “A Common Crises of Public Ethics? Citizenship and Pluralism in Muslim and Western Lands,” Hefner discussed the imperative roles that Christians and Muslims must play in protecting our democracies from discrimination and extremism. Together, these two Abrahamic religions can transform today’s culture wars through democracies built on universal human dignity.

The Bell has distilled Hefner’s lecture into four main questions and reflections.

How can we navigate a political landscape as part of a democracy in which we can’t draw from a shared ethical tradition?

Modern democracies, like the United States, bring together voices from many cultures and religions, which can make it hard for a country to reach political consensus, especially when it comes to deciding how youth should be educated and justice should be enacted, says Hefner. It also complicates conversations about who should be granted citizenship and how they should be treated in society. Before democracies became culturally and religiously diverse, they could base their politics on “a shared ethical tradition like the one that had been provided by religion,” explains Hefner. However, in 2022, Hefner argues that modern democracies have entered an era where democratic values can no longer be based on a common ethical tradition, but instead on prioritized values—the values from our religious traditions that make sense for pluralist democracies and can be extended to all persons in a given society.

Do Christian majorities hurt or help world democracies?

It may surprise people to know that religious discrimination is ubiquitous in Christian democracies. Of the 40 Christian-majority democracies political scientist Jonathan Fox identified, “Thirty developed their democracies under circumstances where religious freedoms were not extended to all religious communities in these societies,” explains Hefner.

This example illustrates the harmful impact Christian majorities can have on society; however, the opposite effect is also true. “Congregational life was one of the first institutions of American democracy,” says Hefner. “It was in congregational worship and assembly that small-town Americans learned . . . the habits of the heart required for self-government and a broadly participatory citizenship.”

When reviewing American history, it becomes clear that Christian majorities strengthened the cause of democracy when operating under Christ’s teachings about universal human dignity, remarks Hefner. It also became clear that Christian majorities work against the cause of democracy when operating under the belief that some people are inherently better than others—and should therefore be treated differently in society. When that happens “Christianity is hollowed out and replaced by identity politics,” adds Hefner.

How about Muslim majorities? Do they hurt or help the cause of democracy?

But Christian-majority democracies aren’t the only ones struggling with harmful identity politics, adds Hefner. The same can be said for Muslim-majority democracies. They too are in the midst of culture wars that are threatening the health and efficacy of modern democracies. For the last 30 years, Hefner lived and worked in Indonesia, a Muslim-majority society with the third largest democracy in the world. One of the tragedies that befell Indonesia after it became a democracy in 1999, after 30 years of authoritarian rule, says Hefner, is that it “led to the proliferation of hundreds of Islamist vigilante groups determined to push back, sometimes violently, against Christians, liberal Muslims and other ‘deviants.’”

Feeling like they needed to protect their people against the Internet, which they saw as a weapon of Western culture to take control of the East, these vigilante groups instated strict Sharia Law and Muslim supremacy. Like many of the Christian-majority democracies today, Indonesia fell into the trap of giving priority to one religious group and persecuting the rest. They became so focused on translating all their religious laws and values into their society that they created a democracy that was more akin to a dangerous prison for non-extremists, says Hefner. “It was evidence of the need for Muslim scholars and politicians to work harder to convince the Muslim public that, yes, Islamic values are vital for modern democracy, but contrary to the radical Islamist claim, the values that are most relevant for today are those that carry over democratic and inclusive values into the very heart of Muslim ethical and political life,” says Hefner.

If Indonesia wanted a healthy and effective democracy, explains Hefner, their leaders—political and religious—would need to move from an emphasis on punishment to the higher aims of Islamic law, which are very compatible with democracy and the belief in universal human dignity.

How can we protect our democracies from raging culture wars?

If we want to live in a democracy where people have true religious freedom and equal human rights, then we need to prioritize what we value, urges Hefner. We can’t bring everything we value into the political landscape if we want there to be enough room for everyone to thrive, which means that Christians and Muslims must focus on the higher aims of their religious traditions, principally anything that supports the belief in universal human dignity.

“In such an age of religiously leveraged identity politics, it becomes all the more imperative for democratic-minded people of faith to work from within their traditions to make sure that we get the higher aims of our own religious and ethical traditions,” asserts Hefner. “That’s our challenge. We need to build an overlapping consensus that prioritizes freedom, dignity, equality and solidarity across social difference rather than the exclusion of those who don’t look like us or come from a different faith tradition.”

You can watch Hefner’s entire lecture on Gordon’s YouTube channel sometime next week, so be sure to subscribe!

The Bell

The Bell