From the Cradle to the Grave: Newborn Humpback Whales and Dearly Departed People

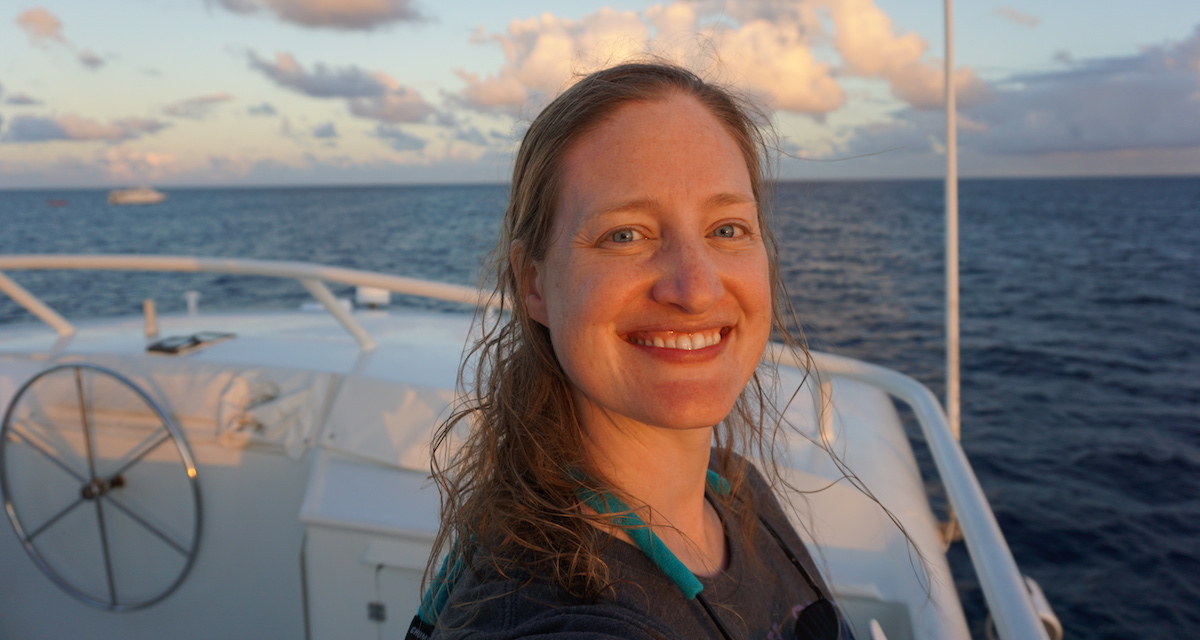

In February, Mindy Hofsass ’04 locked eyes with a curious humpback whale calf through her snorkel mask in the open ocean of the Silver Bank Marine Mammal Sanctuary just 80 miles off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Every winter and spring, between 5,000 and 7,000 humpback whales pass through this 40-square-mile stretch of ocean to mate, give birth and raise their young.

As a tourist in one of the few places on Earth where swimming with humpback whales is both lawful and humane, Hofsass spent more than 28 hours over the course of five days in and on the water with these gentle giants, waiting for them to approach her—as is custom in the “soft-in-water encounter” created by Silver Bank whale naturalist Tom Conlin.

“It’s one thing to see the humpback whales from the surface,” Hofsass says, recalling the semester she spent working for Yankee Fleet Whale Watch in Gloucester, MA, during college. “But to actually be in the water with them—you can’t really describe how that feels. They are so graceful.”

For Hofsass, this trip tapped into a lifelong fascination with marine creatures—one that had inspired her to study marine biology at Gordon and go on to work as a seasonal marine mammal trainer for the Hersheypark Aquatheatre.

But, when Hurricane Katrina wiped out the company’s largest marine mammal park in Mississippi in 2005 and the animals had to be permanently relocated, Hofsass went from being a caretaker of dolphins and sea lions to being a caretaker of the dead—and their living loved ones.

Finding a home in funeral work

At that point, Hofsass took a part-time job at a family-run funeral home as a temporary fix. But when she worked her first funeral, Hofsass realized that she somehow knew what to do when it came to helping people who were grieving. She knew when people needed a bit of levity, a sense of order, or someone to humor their, at times unusual, requests—even when it meant putting a working cell phone in a casket with a year-long phone plan. And 13 years later she’s now the full-time assistant to the funeral directors.

Like an on-call physician, she’s available 24/7—except on the nights she has off to teach her ballroom dance classes at PA DanceSport, where she has been an instructor for nine years.

She is, in her words, a social worker for the bereaved. While her workday can consist of picking up decedents and helping with the embalming process for burial, most of her work hours are spent aiding the living. She performs the tasks that need to be done—rounding up death certificates, coordinating funeral details and putting together tribute videos—so that the bereaved can grieve their loss without having to worry about the logistics of death.

“People ask me, ‘How do you do this? You’re dealing with death all the time,’” says Hofsass. “Really, taking care of the deceased is just one small aspect of funeral work. Death is involved, clearly, but you’re really dealing more with the people that are still here. It’s more of a ministry to hurting people. We’re helping them get through what is, for some of them, the worst part of their lives.”

Mourning and rejoicing

Sometimes, as both funeral director assistant and ballroom dance instructor, Hofsass feels like she’s living a double life—especially when those two worlds bump into each other from time to time.

“People don’t realize I kind of have this dual life. So, when one of my dance students sees me at a funeral, it really throws them for a loop and vice versa. Sometimes people stare at me and wonder ‘Where do I know this person from?’ All I have to do is stand in a ballroom pose and they’re like ‘Oh yeah!’”

Here Hofsass is competing in Pro/Am International Style ballroom dance at the 2010 Capital DanceSport Championships Competition, where she won first place in her division. She’s now retired from several years of competitive ballroom dancing.

In some ways, she’s two sides of the same coin—mourning with those who mourn and rejoicing with those who rejoice. As a dance instructor and funeral director assistant, she is helping people prepare for their first wedding dance and their first memorial service.

Like humans, like humpbacks

As it turns out humans aren’t the only ones who mourn their dead or dance with their romantic partners—humpback whales do too. They cry when their calf dies and when their companions are beached in shallow water. And during courtship, in the warm waters of the Silver Bank, they can be found performing an elaborate underwater “waltz.”

During one of Hofsass’s many whale encounters in the Silver Bank, she recounts the act of a mother whale lifting her young calf to the surface so that it could breathe when it was too tired to keep swimming.

“These animals have an emotional aspect to them. It’s pretty incredible.”

In the parts of her life that, at a first glance, seem unrelated—funeral work, ballroom dancing, marine science—Hofsass finds great continuity. She sees a continuum that stretches from an ocean nursery, to a dance floor, to a cemetery that involves many kinds of emotionally-complex creatures, whales and humans included.

The Bell

The Bell