How the Pandemic Changed the Tune for Gordon’s Musicians

This is the first article in a series highlighting how Gordon’s fine arts departments have creatively adapted to the constraints of COVID-19 precautions.

Aspiring musicians spend their learning years seeking out opportunities that offer insights into the lives of professionals. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Gordon’s Department of Music students and faculty alike found themselves in the company of the world’s greatest musical names for perhaps the most unique master class of their careers.

As creators of an artform that requires close proximity, studies on the spread of COVID-19 through aerosol dispersion meant that business as usual for the Department—and musicians around the world—suddenly became a serious health risk. So, after classes went remote last spring, Adams Endowed Chair in Music Sarita Kwok and her colleagues spent the summer devising a seven-page manual of COVID-19 safety guidelines and preparing for a fall semester that would stretch their creativity technically, artistically and spiritually.

Different daily rhythms

Initial mysteries surrounding the spread of COVID-19 prompted the Department to adjust protocols according to research as it became available. The goal, says Kwok, was “to be extremely cautious in safeguarding students’ health and the health of our faculty, while also ensuring that we were keeping the music alive.”

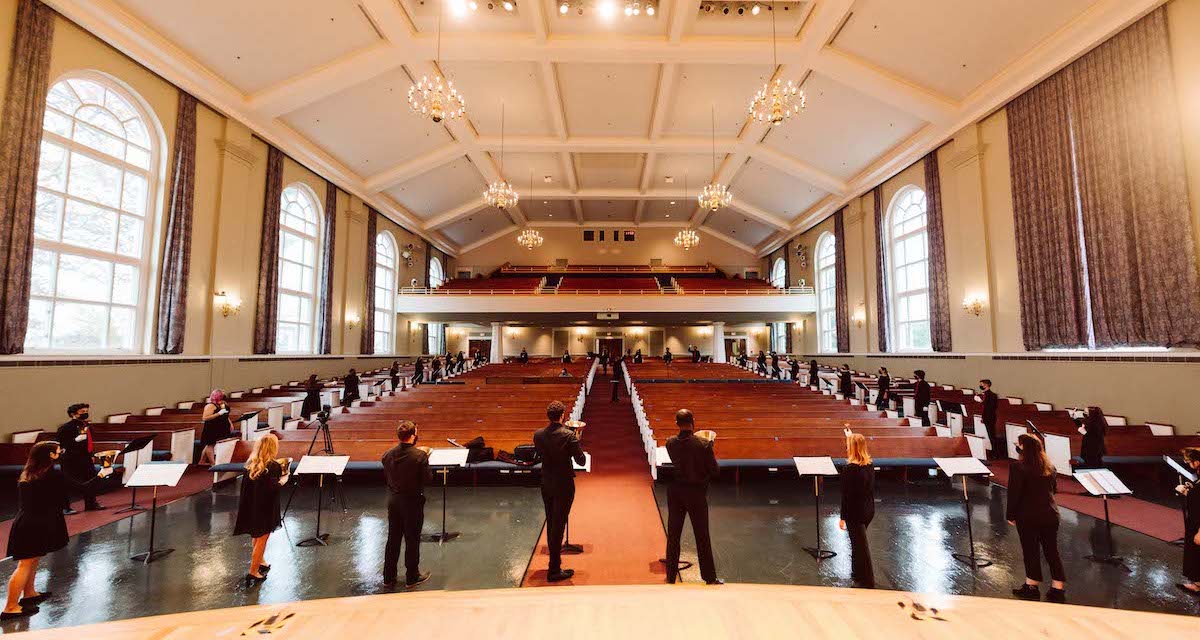

Some lessons and rehearsals moved online to Zoom, but the majority of music classes and rehearsals remained in person with distancing ranging from six to 15 feet apart depending on the delivery method and personal concerns. For example, the larger ensembles filled up the entire A. J. Gordon Memorial Chapel and practice rooms designated for music majors and minors required advanced reservation, sanitation between bookings and up to one hour of post-practice vacancy.

Wind instrumentalists wore special face coverings that feature a small slit to access the mouthpiece. Even instruments donned masks—brass instruments were given bell covers, outfitted in marching band-style covers. Flutists were positioned behind plexiglass barriers for extra precaution since early studies indicated flutes might project more aerosols and bell covers would not fit.

Because singing spreads COVID easily, says Instructor in Music and Women’s Choir Director Faith Lueth, “the impact on the singing world has been huge.” She split her students into three groups, and for each rehearsal one joined Accompanist Ya Lin Huang in the Chapel, a minimum of 12 feet apart and masked. “We’ve had to rethink our way of doing things,” Lueth says.

Casting a new artistic vision

Once new protocols were in place, students encountered new kinds of lessons—performing with masks on and at a distance prompted faculty to emphasize important musical skills like diction and non-verbal communication even more than usual.

“One of the things that has been really rewarding to see among the students,” says Symphonic Band and Symphony Orchestra Conductor Benjamin Klemme, “is their ability over many weeks to adapt to the distance at which we’re playing and to strengthen their already excellent communication skills in order to be able to communicate to the same degree at greater distances.”

While pivoting to livestream and virtual experiences to avoid large gatherings meant no spotlight or applause, it opened doors for new opportunities and engaging broader audiences than ever. Not only could families across the globe watch their students perform, but special guests could collaborate.

“I think we’re doing things with technology that is positively impacting how we make music. Things that we would not have done before because we were not faced with the challenges of this current situation” says Kwok, “necessity being the mother of all invention.”

Recognizing that pandemic meant many high schools would have to forego performing, the Symphonic Band hosted 35 students from across the nation for virtual tutorials, rehearsals and a performance of John Philip Sousa’s “The Invincible Eagle.” Klemme also took advantage of Zoom by inviting special guests to share insights with his Arts in Concert course, including Boston Ballet Music Director Mischa Santora, who spoke about Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, and Boston Lyric Opera Music Director David Angus, who spoke about talked about Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

“Some of the things that we’ve been able to explore and discover . . . have been surprising and unexpected,” says Klemme. “And sometimes the greatest discoveries are unexpected.”

For the students in Women’s Choir, one of those discoveries was an even more rich spiritual experience. Because protocols only permitted them to sing for 30 minutes, rehearsal time allowed them to dig deeper into Scripture and the background of their music, like “Total Praise” by Richard Smallwood. Lueth says the women related to Smallwood’s resolution to praise God amid difficult circumstances—he wrote the song in 1995 while serving as caretaker for both his sick mother and terminally ill godbrother.

“Out of that situation came the song,” says Lueth. “We talk[ed] about why we praise. It’s not a pity party but praising—really thanking the Lord and praising him for who he is.”

The Bell

The Bell