Making Stars for the Next Moon Landing

Fifty years ago, when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin planted an American flag on the moon’s powdery surface, the stars were a little lackluster, especially in retrospect. The difference between the stars of 1969 and those of today is a small one, but nothing short of iconic. In 1973, the son of a Swiss immigrant convinced the oldest and largest American flag manufacturer to put embroidered stars on the American flag and forever changed the look of the nation’s symbol. That man was former Gordon Divinity School student Art Stucki x’58.

Seventeen years before Stucki pitched his idea to Annin Flagmakers, he came to Gordon with the hope of rebuilding his faith. With a Bachelor of Arts in anthropology and a knack for languages, he opened himself up to a future in Bible translation with Wycliffe. But after a year at Gordon, he felt that God was calling him back to the embroidery factory he’d lived above for nearly 20 years—back to a trade he knew nothing about.

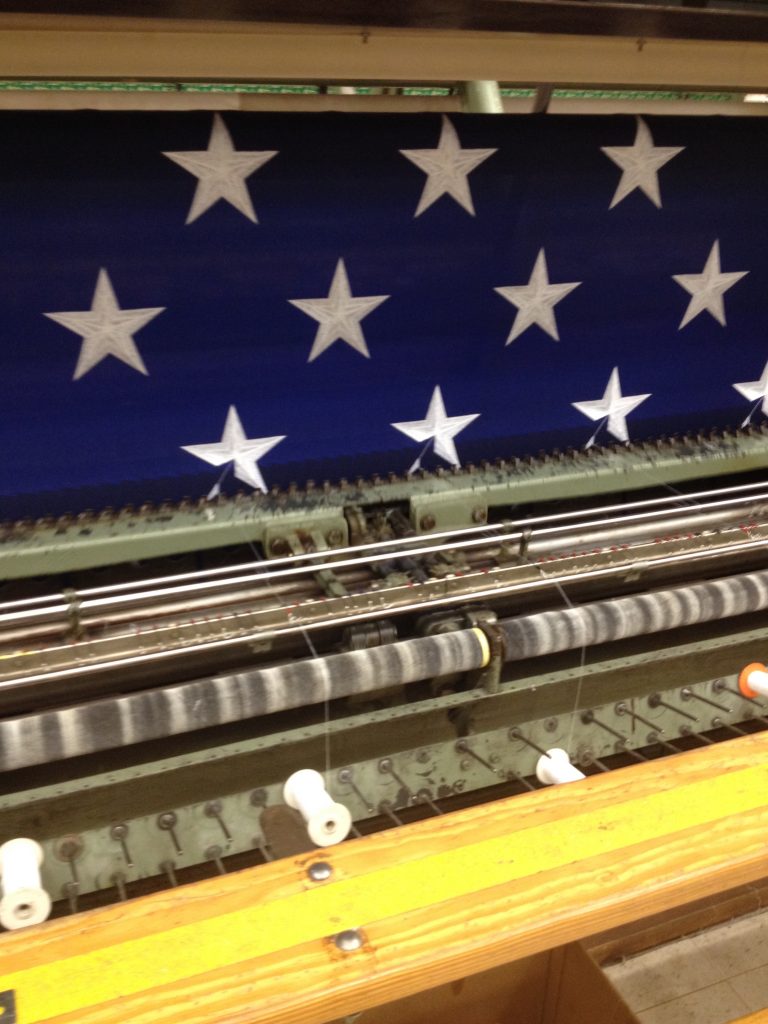

It took him six years to learn his way around the 15-yard-long Schiffli embroidery machines (large enough to take up an entire lane in a bowling alley). And then the industry changed fundamentally. Their largest clientele—the textile and garment makers of New York City—were moving production to China where everything from labor to materials was cheaper.

At the same time, social movements like feminism changed the way people dressed. Suddenly, lace and detailed embroidery stood for the Cult of Domesticity and the feminine conventions many women were trying to break out of.

What Stucki needed was a product that would never go out of style or overseas. And the American flag was perfect. It was one product that, on principle and by law, couldn’t parade around the U.S. in a Made in China sticker—at least not for many years. He promised Annin “a more beautiful American flag,” and he delivered on that promise.

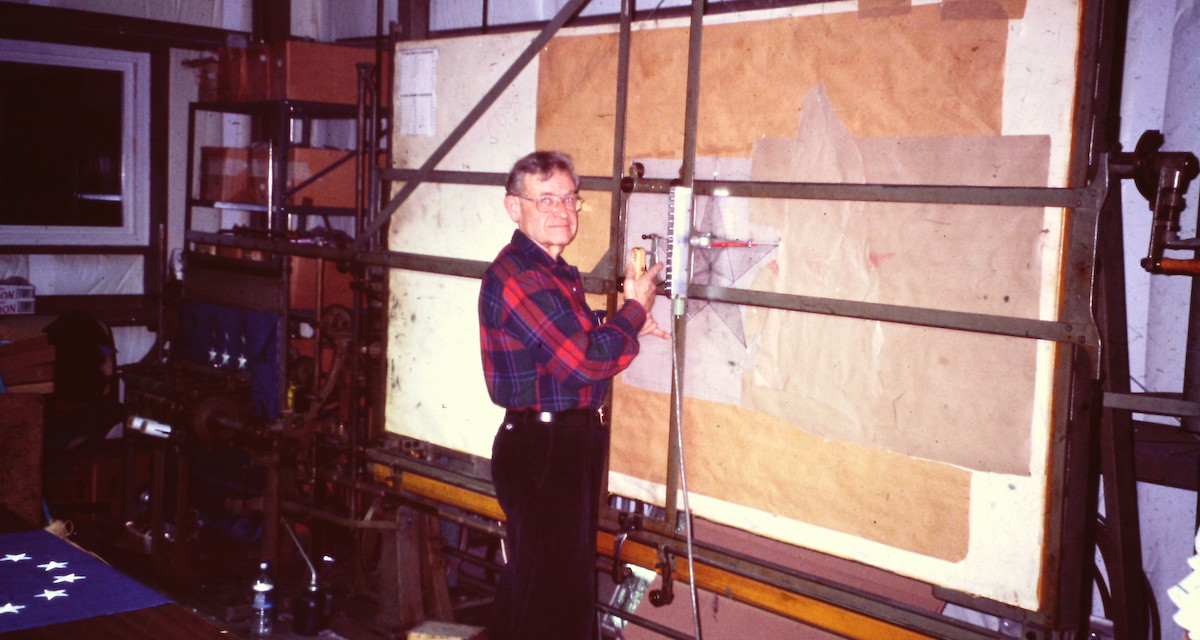

Within the year, Stucki and his team were embroidering 1.5 million stars onto 30,000 flags every week. At one point in U.S. history, one out of every seven flags sold in America had stars that were embroidered at Stucki Embroidery Works (which later became SEW Inc).

“The Swiss machines had a special attachment that I used for the stars,” explains Stucki. “A flag has to look nice in the front and in the back because you can see both. With most embroideries, it doesn’t matter what’s on the back. Nobody will ever see it. But, I could make the stars shiny on both sides.”

Because most American embroiderers had machines without this special attachment, it never occurred to them that they could make a business out of embroidering stars onto the American flag. In other words, Stucki had found a niche—one that had served him well for almost 40 years.

In the two days following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Walmart sold a million American flags. Each one of them had Stucki’s stars.

But flagmakers weren’t their only new clients. Over the years, custom orders came in from the White House, the Vatican and even Walt Disney. Stucki and his brother-in-law and business partner Murray Fenwick ’64 (who took over the business in 2000), embroidered presidential seals for several U.S. presidents (such as Bill Clinton and George H. W. Bush), clergy-wear for the Pope and cardinals, and even dress trains embellished with real gold thread for the many Cinderellas of Disney Land and Disney World.

“I was quite proud to see the Pope and cardinals wearing vestments with our embroidery when there were so many embroiderers—that the Catholic Church would choose us,” says Stucki.

Eventually the domestic flag-making industry fell prey to new consumer habits and savvy business practices. Flagmakers, like Annin, purchased their own embroidery machines and American consumers opted for Chinese-made American flags to save money. In 2015, the Embroidery Capital of the World lost its poster child; Stucki Embroidery Works closed its doors after a 90-year-run.

To think that the family factory could have closed in the 60s—without making history by way of the American flag, the Catholic Church or Walt Disney—is remarkable. The domestic flag-making industry gave Stucki Embroidery Works a second wind and a family legacy that is still visible in the millions of stars overhead with a thread count, if you only know where to look.

This year NASA announced that in 2021 they are sending a woman to the moon. Not only will she be the first female astronaut to perform a lunar landing, she’ll be the first person to reach the moon after a 45-year absence. When she does, chances are she’ll plant an American flag into the moon’s powdery surface once again, but those stars will be everything but lackluster.

The Bell

The Bell