The Redemptive Side of Anger: How Civil Rights Activist Arthur Whitaker ’49 Used His Own Pain to Bring About Healing

In honor of Black History Month, The Bell revisits the inspiring story of Rev. Dr. Arthur L. Whitaker ’49, a Gordon graduate who worked tirelessly for racial equality and the “brotherhood of all men” during World War II, the Civil Rights Movement and the many decades that followed.

Martin Luther King (front and center) during his 1958 visit to Rochester. Arthur Whitaker is to his left, one row behind, numbered 16. Photo was taken by Rochester Police Officer Charles Price.

Three years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. organized the bus boycott in Montgomery and five years before he was arrested in Birmingham, he was in the car with his friend Arthur Luther Whitaker ’49 who’d offered to take him to the airport after a speaking engagement in Rochester, NY, in 1958. On the way, they stopped by the church where Whitaker pastored. Upon seeing the church, King asked Whitaker, “What kind of preacher are you?”

King had heard Whitaker preach several times before—when they had shared a rostrum at a black church in Portsmouth, NH. Plus, the two had met as graduate students in Boston in 1952 after King had invited Whitaker to be part of his informal Negro Philosophy Club—so King had heard Whitaker express his faith innumerable times, in the company of the Boston’s few black seminary students. But now, perhaps given time apart and the great distance that separated them, King was curious to know what kind of pastor Whitaker had become.

“Well, I’m not a whooper,” joked Whitaker. “I guess I’m sort of a dynamic preacher.”

To which King replied, “I’m a dynamic preacher, too.”

Although it’s undeniable that King and Whitaker had a natural talent for oratory and the pastoral training to go with it, their dynamism did not come from those two sources alone. It grew out of adversity—fueled by righteous anger (about the racial injustices they and their communities had experienced) and also a strong Christian faith, which—together—had the power to transform feelings of hatred into a desire for equality.

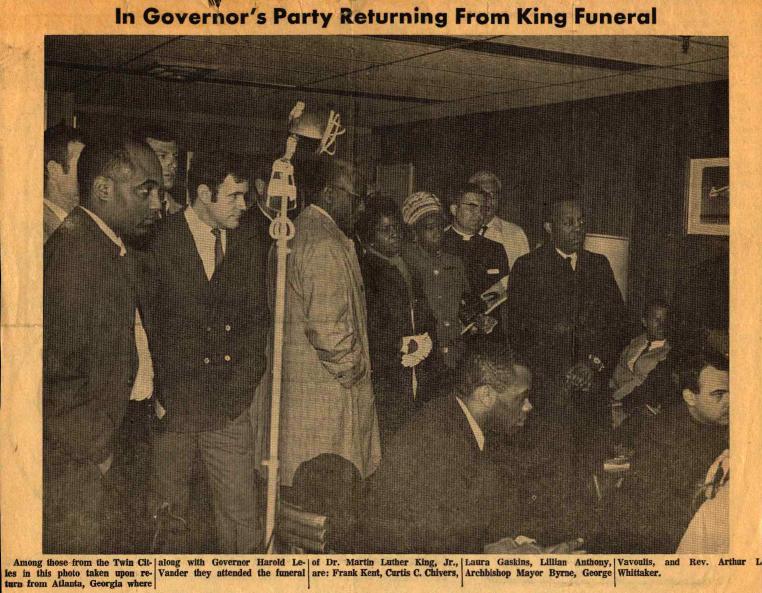

Newspaper image of Arthur Whitaker (pictured far right) at Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral in Atlanta, Georgia on April 9, 1968.

In 2020, these two civil rights leaders remind us that when we are angry, we have a choice. We can use our pain to justify our hatred of another or we can use it to try to turn our enemies into allies—to solve the problems that are at the source of our pain.

Racism Mirrored in Hitler’s Germany

Whitaker first experienced racial prejudice as a black child growing up in the mostly white neighborhood of Malden, MA. But he didn’t think about racism in America seriously until he was drafted into the Army during World War II as part of an all-black combat division.

He served overseas in Tunisia, Naples-Foggia and Central Europe, but he was stationed in Germany the longest—one month before the war ended and then seven months after.

Whitaker recorded his memory of Hitler’s Germany in a research essay—a psychological analysis of the Civil Rights Movement titled “Citadel of Tragedy.” In the introduction, he wrote, “On every occasion in which I had the opportunity, I asked why the German people allowed Hitler to hate and kill 6 million Jews. The answer was always the same—‘We could do nothing.’ I tried to search for some thread as to why Hitler and the nation hated the Jews. In reality, I was also asking why does AMERICA hate Negroes as I searched for my own identity in those early years of maturation. . .”

No matter how many times he asked the question, the German people could not give him the answer he so desperately sought, so he searched for it elsewhere—in academia. First, Gordon College, then Harvard Divinity School, Andover Newton Theological Seminary and finally Syracuse University—earning a Ph.D. in sociology. When King visited him in 1958, Whitaker was the pastor of Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, a civil rights leader and a lecturer in sociology at Rochester University.

A Voice of Reason in a Time of Unprecedented Violence

On a record-hot summer’s day in Rochester on July 27, 1964, a riot broke out and this time people went to Whitaker for an explanation.

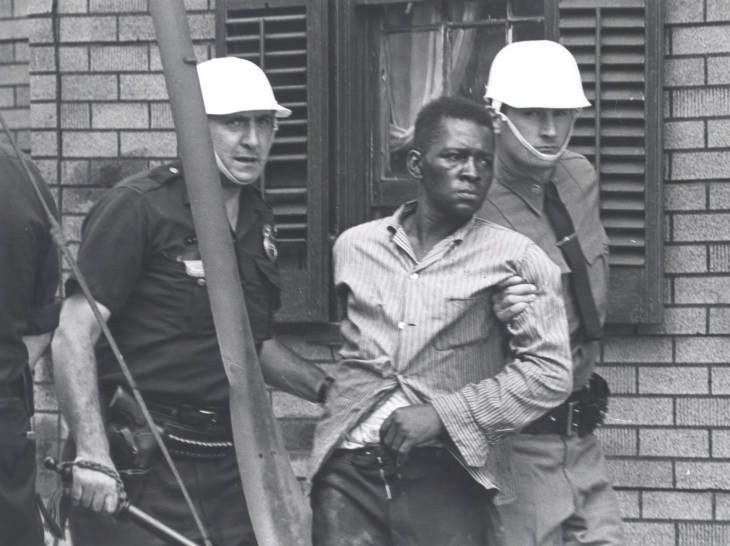

Police on Joseph Avenue at Ward Street after the 1964 riot in Rochester, NY. Photo courtesy of Rochester Municipal Archives.

Over the course of three days and two nights, 1,000 people were arrested, hundreds were injured and four were killed. It was, at that time, the most violent occurrence in Rochester’s history—only contained after the governor called in the New York National Guard—the first time American troops had been used in a northern city since the Civil War.

Given its national publicity, Whitaker was asked to analyze the riot as a black sociologist for THE CRISIS, the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) based in Baltimore. His analysis, “Anatomy of a Riot,” eventually earned itself a place in the Congressional Record.

Two police officers lead a man away after the Rochester riot of 1964. Photo Courtesy of Rochester Municipal Archives.

If the city wanted to prevent future riots and improve race relations in Rochester, wrote Whitaker, they had to address the problems that drove people to riot in the first place—problems like overcrowding in black neighborhoods, a segregated public school system and police brutality against black residents.

In “Anatomy of a Riot,” Whitaker explained, “The ‘why’ of any catastrophe is never easy to answer . . . Violence is nurtured in an atmosphere of unrelieved frustration, resentment and despair. Violence does not provide the answer nor can it be condoned. Violence, of course, is not uniquely Negro; it breaks out among other ethnic groups and in all socio-economic classes. But last summer’s riots in Rochester, New York; Philadelphia; and elsewhere were rooted in the social and economic disadvantages foisted upon the Negro by an apathetic, if not insensitive, society.”

Pastor, Public Servant and Poignant Witness

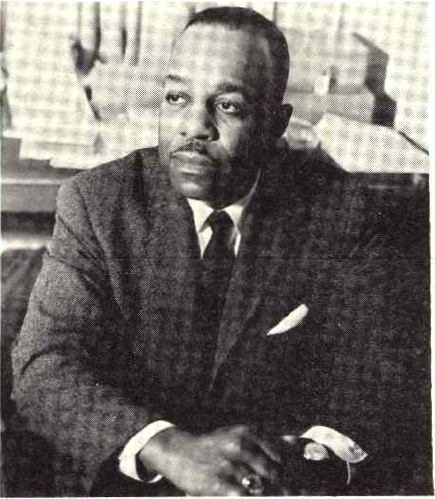

Portrait of Arthur Whitaker printed in The Human Relations Reporter in January of 1970 (VOL. XII, No.7)

In attempt to change apathetic and insensitive minds, Whitaker told stories of his own hardships—as a soldier who fought in a segregated army, a parent of four children being educated in a segregated school district, and as a resident of a segregated city that prevented the black middle class from leaving low-income neighborhoods and making a home in suburban ones. He shared many of these stories with U.S. Congressmen and local government officials, eventually persuading them to investigate racial discrimination within the American military, cease nuclear warfare after the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and even make Martin Luther King Jr. Day a legal holiday in the state of New York—knowing it would pave the way for King’s birthday to become a national holiday, which proved to be true.

In 1959, he became the first black man to be appointed to the formerly all-white Rochester Rehabilitation Commission, and as such, he was able to make the city aware of how racial discrimination was creating an economic and housing nightmare for Rochester’s black residents.

His voice became so significant in these matters that on September 16 and 17, 1966, Whitaker testified in a hearing conducted by the United States Commission on Civil Rights to the racial segregation that was still present in Rochester public schools, neighborhoods and places of work.

Anger is Useful—When You Know How to Use It

For more than 30 years of his life, Whitaker was also a pastor. In his sermons, he told stories and provided guidance for how his congregants might use their anger as energy for redemptive work.

Fifty-one years ago, this very month, Whitaker gave a sermon called “The Christian God in the Black Community”—and yet his words are just as relevant for us today as they were then. In what some journalists are calling the “Age of Rage,” a time when the world’s citizens are saying they’re angrier than ever before (Americans included), Whitaker offers us perspective on our growing sense of frustration.

First, it isn’t wrong, or sinful, to be angry. Our feelings are there for a reason (they stem from a real problem). And secondly, anger is useful. It has the power to stir up hatred or inspire us to come up with a moral solution. It can drive us apart or bring us together.

In this sermon, Whitaker concluded saying, “There are no panaceas for the crisis facing us and our time, nor are there any quick remedies for the total problems facing all mankind . . . Let it be said of America that in spite of her dilemma she was able to outlive her racism and bigotry, and live out her destiny of the American Dream that future historians will say of us that in the period of crisis we were able to resolve our differences and solve our problems of race and inhumanity, and in the process together we achieved the finest hour in human history.”

The Bell would like to express thanks to Jessica Suarez, the curator of manuscripts and archives at Andover-Harvard Theological Library, for making Arthur Whitaker’s sermons, essays, articles and pictures available to us; to Director of Worship and teacher of racial conciliation Bil Mooney-McCoy, for offering his input on this article and making sure it stayed true to Whitaker’s original message; and to Gordon College Archivist Sarah Larlee for putting Arthur Whitaker back on our radar—and getting us started on this journey of mining the past for the sake of the present.

The Bell

The Bell