Changing the Tune of Representation in Classical Music

“Wer weiß woher ich komme?” “Who knows where I’m from?” Michael Ellis Ingram ’08 asked the children in his music workshop. “Paris,” shouted one; “Tokyo?” guessed another. “Schwerin Central Station!” declared a third. A Black Missouri native in Germany, Ingram was touched that he had apparently absorbed so much German culture that a young boy would think Ingram was born in his hometown.

“That’s really powerful because the people who were born where you were born—you have no fear of them,” says Ingram. “That is a dimension to empathy that could really be powerful in shaping the way that people interact with each other, if they’re different in some profound ways.”

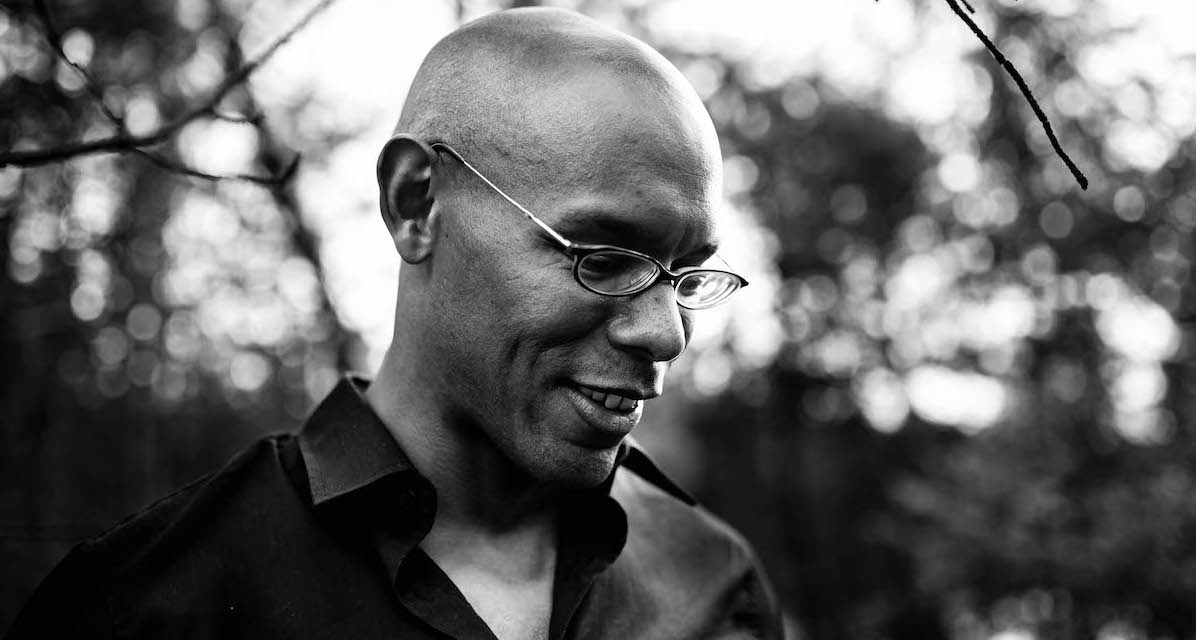

Embracing being Black has been a lifelong journey for the Department of Music alumnus, who moved to Germany in 2010 to pursue a career in music. As the kapellmeister and solorepetitor of Staatstheater in Schwerin, Germany, Ingram is a vocal coach, conductor, pianist and composer for operas, ballets, musical theatre, children’s concerts and more. His prestigious and unique role combines his greatest strengths and the aspects of music he loves most, embodying a professional diversity he also treasures personally.

A personal crescendo

But if you had asked Ingram about the experience of being Black in the music world even two years ago, he would have told a much different story about his ethnicity. Growing up surrounded by White people in Columbia, MO, “I very quickly learned the quickest way to make White people uncomfortable is to talk about race,” he says. “How does that make me feel?” In what Ingram considers this first phase of grappling with his identity in his youth, he says “I basically pretended to be White.”

Later when he realized that pretending didn’t change reality, Ingram accepted being Black—but relied on humor to diffuse discomfort. “I often would just say innocent, lighthearted things like, ‘I’m white on the inside,’ which in retrospect was profoundly damaging to myself,” he says. “How long can you go on as a human being telling yourself and those around you, that you are something else on the inside, but that’s not true?” His approach extended to music, too. “‘What is it like to be a Black conductor?’ I always hated that question because I wanted people to ask, ‘What is it like to be a conductor?’”

Changing his tune

Ingram recently entered what he says is a new, healthier phase in accepting and embracing the beauty of being Black. And when protests advocating for racial justice took center stage last summer, he tried to capitalize on the momentum by calling up friends to finally have real, productive conversations about race.

“I am a Black person,” Ingram says. “I am a Black conductor and that carries with it a very particular type of experience and a very particular weight of history. And if I don’t talk about it the right way, then no one will.”

A new song

Acknowledging his responsibility, Ingram also began to rethink his own musical pedagogy and how he portrays diversity—of race and gender. “It takes no work to know who Tchaikovsky is,” he says, “but to know female composers or Black composers—that takes work. You have to go digging.”

“I have always taught music history as basically a parade of dead White guys and all of the great things they did,” Ingram says. “And they were great. But we’re only looking at a tiny sliver. I am interested in looking at all of it. What I try to remind myself and other people is that diversity is not a niche issue. It’s about finding the greatest music and the greatest musicians that are out there. And if we’re only looking in the rubric of old White dudes, then we won’t find it because that’s a tiny fraction of the population.”

Ingram acknowledges he cannot instantly expand the classical music canon—the set of works performed by every orchestra in the world. But he aims to get there by performing, advocating for and teaching about composers on par with household names but whose legacy did not make it into the standard repertoire, like Mozart’s contemporary Joseph Bologne and 20th-century composer William Grant Still (hear compositions by both performed by the Gordon Symphony Orchestra on March 27).

“We never went away, but the canon didn’t have room for us,” says Ingram. “Society has a certain image of what a composer can or should be. And thankfully, that’s being shaken up.”

Header photo by Tim Gassauer

The Bell

The Bell