Opening Wide the Door to the Great Outdoors

This article originally appeared in the spring 2021 issue of STILLPOINT, the magazine of Gordon College.

50 Years of La Vida

The rugged, grassroots efforts that teetered on the brink of failure, and came back to transform thousands of lives.

There are a few ways to build a trail. One option involves trail designers, careful plans and construction. Another may start with similarly careful plans but divert over time; “social trails,” as they’re called, are created gradually as hikers step around a puddle or a downed tree. Sometimes they’re simply shortcuts. Then there’s the bushwhack—an opportunity to leave the traditional trail and forge your own using only a map and compass. This most rugged option requires grit, determination and a clear vision. And that’s how La Vida was born. A few trailblazers with a passion for the power of faith-based experiential wilderness education muscled their way through uncharted territory, enduring all the scrapes, scars and victories that come with pioneering new pathways.

In the mid 1960s, Dean Borgman, then on staff with Young Life—a nondenominational ministry to high school students—was working with the followers of Malcolm X after he had been assassinated. “They had some very radical ideas about Black youth and the Black youth crisis,” Borgman says. “They thought these young African Americans—some of their parents had come from the South—were suddenly thrust into urban living. And they were very strong, as we had these late-night conversations, about getting Black youth back to the land and to the sea.”

In response, Borgman, along with his colleague Bill Milliken and their Young Life trainees working on the Lower East Side of New York City, developed what Borgman called an “alternative plan for camping—a wilderness adventure type of camping, although we knew very little about it at that time.” The trainees, called the Lilly White Boys because they were funded by the Lilly Foundation, had attended an Outward Bound experience in Colorado, which fueled the inspiration for a wilderness experience.

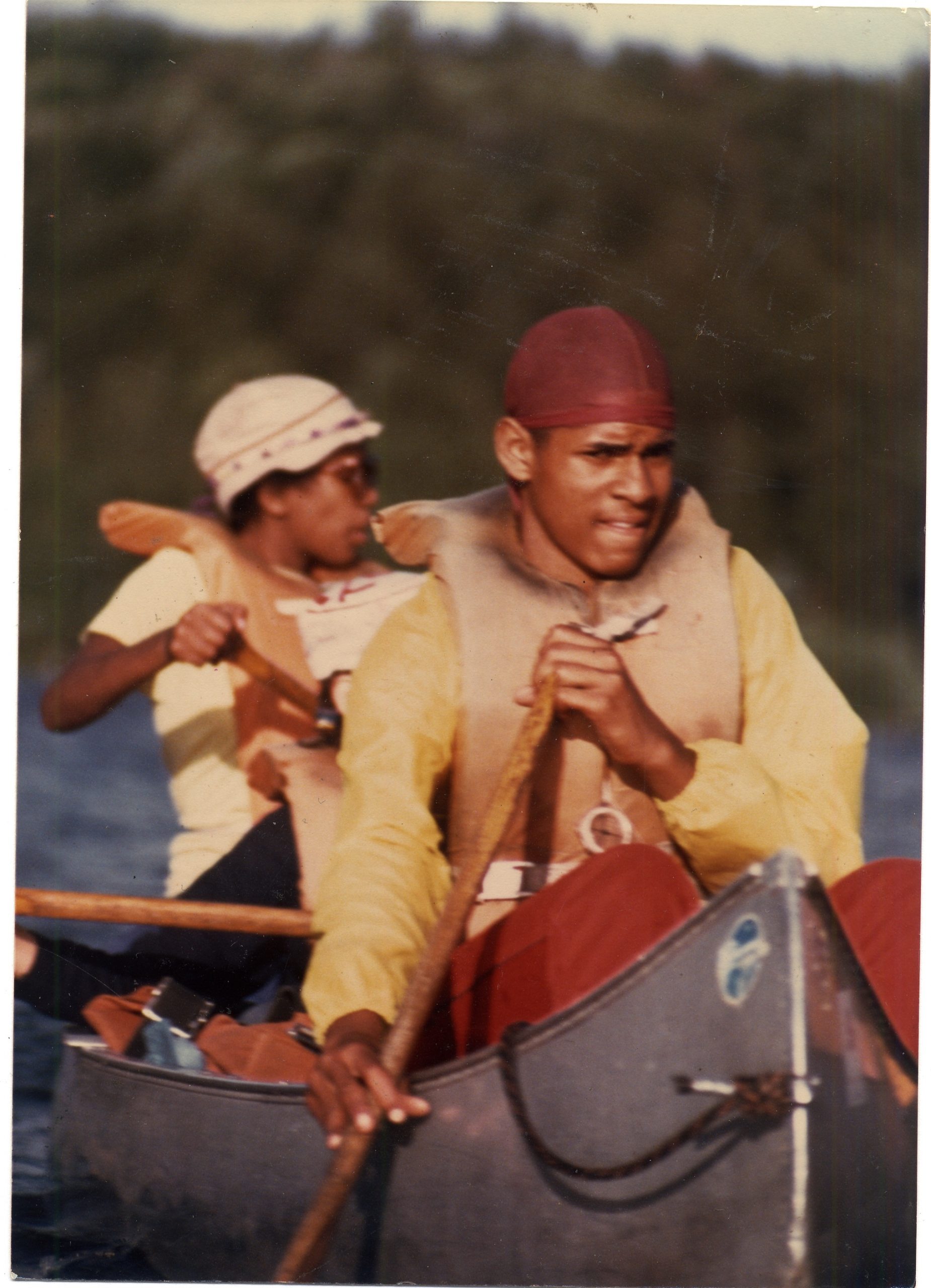

Using Young Life’s Saranac Lake, New York, campground as base camp, the inaugural 15- day La Vida expedition set out in the summer of 1970 with 16 participants from Harlem, a German Shepherd and two leaders: Colorado Springs Young Life staffers George Sheffer Jr. and Jim Koontz, who had also worked for Outward Bound in Colorado. Recent college graduates and fellow Young Life staffers Steve Oliver and Tuck Knupp also joined to catch the vision for this new camping ministry. On this very first trip, the solo experience and 10-mile run were born.

Legend has it that La Vida’s name was, too. The Harlem group included several Puerto Rican youth, who under the tapestry of stars and quiet crackle of the fire in the Adirondacks concluded, “Eso es la vida”—this is the life. Borgman’s version differs a bit, as he recalls one of the Hispanic Young Life leaders, Ricky, shouting the name in response to the original proposal for alternative camping.

Either way, La Vida stuck. In time, its original vision took a “social trail” deviation, if you will. Its bent as an experience specifically for youth in city areas shifted as Young Life began to align what they called their “creative camping options”— including La Vida and similar ones in North Carolina, Colorado and British Colombia—into follow-up discipleship experiences for participants of the traditional Young Life camps.

By that point, Borgman had moved on to teach at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and establish a Young Life training program there (though he remained on the La Vida board), and others entered the La Vida scene. Oliver along with Scott Dimock, an outdoor enthusiast and Young Life staffer based in Washington, D.C., thought La Vida could benefit from the help of their friend, Colorado Outward Bound School instructor and former Army Ranger Dr. James Kielsmeier.

“The Young Life work in the city at the time and my work in Outward Bound clicked around the fact that we were very keen on the wilderness experience being a time for bringing [together] young people of different races and cultures from a social justice perspective,” says Kielsmeier.

The potential for creating a “shared meeting ground in the neutral territory of the outdoors,” as Kielsmeier described it, combined with a memorable adventure and lasting discipleship experience united this otherwise disparate group of trailblazers.

By the mid-70s, Kielsmeier and Dimock were infusing La Vida with necessary staff development and wilderness program skills, elevating the discipleship component and raising money to expand the gear supply. They redefined the role of trip leaders, dubbing them “sherpas,” and introduced the two prongs of mountain patrols and canoe patrols.

Around this time, a punchy seminarian from Virginia by the name of Richard Obenschain was introduced to the program through Borgman’s Young Life training program at Gordon-Conwell. Obenschain had been working for the Scotsman Adventure School, which became Project Interface at Gordon College, and was eager to play a role in the strengthening of La Vida.

In one of Kielsmeier and Obenschain’s first shared endeavors, the pair led minimum-security prisoners on adventure days, including ropes course and group activities. When Kielsmeier pitched the idea to the prison superintendent

in Ray Brook, New York, he says the superintendent gave him one rule—“You can’t use a map and compass; you can’t teach the inmates how to escape”—and then granted him permission. “The reason I want you to do this,” Kielsmeier recalls the formidable superintendent saying from behind his colossal wooden desk, “is because you’re Christians . . . Over half the people who leave this place on release are going to come back and be readmitted. But I know for a fact that half who leave here with a faith grounding, with a faith base, will never come back.”

La Vida’s current executive director, Abigail Stroven, remembers the late Obenschain retelling the experience of guiding the prisoners over “The Wall,” an activity wherein the group works together to scale a 12-foot structure. In retrospect, he would say, “I am not sure we were supposed to be teaching them how to do that, but the guards were with us, and they didn’t say anything.”

The experiment was a success, and it was repeated multiple times. As a thank-you, the prisoners built a bridge over a swamp to connect the Young Life Saranac Lake camp to its nearby ropes course and dedicated it to La Vida.

By 1980, however, “Young Life had carried it as far as they were going to be able to carry it from an administrative standpoint. We had really bolstered it in terms of its program side, but on the administrative side . . . it was cumbersome,” says Kielsmeier.

Young Life shut down La Vida. But Kielsmeier, Dimock and Obenschain banded together, motivated by their belief in the transformative power of both wilderness experiences and the gospel, and their drive to make such experiences accessible to all. They knew the program could—in fact, had to—stay afloat.

At Obenschain’s suggestion, they explored the idea of bringing the program to Gordon to join forces with Project Interface. After two years of an uncertain future, La Vida finally found a home. But the fight to survive wasn’t over. For the next several years it would endure a steady uphill battle to be fully adopted by the College—eventually earning a spot in the Core Curriculum with the addition of Discovery and Concepts of Wellness course options, and adding GORP (now Adventure Pursuits) to serve churches and other groups.

Even as La Vida was getting its sea legs at Gordon, the program continued to welcome all into the wilderness. In the mid-80s, Dr. Diana Ventura ’88, a physical education student with cerebral palsy, spearheaded the idea for an expedition for students with disabilities. At that point, La Vida was a requirement for physical education students but not yet for all students. She could have received a waiver, but “I wanted the gift of [La Vida],” she says. “I saw it as a way to be out in nature and to respond to a challenge that was presented before me.” So, Ventura took it upon herself to convince four fellow students with disabilities to join her, along with six able-bodied students, on a canoe patrol.

“We had the full La Vida experience,” including solos, says Ventura. She crawled up the 2,876-foot Mount Jo on hands and knees; Obenschain scaled the rock climb at Owl’s Head with one of the participants strapped to his back.

“My whole life is a walk in faith that bucks against the idea that what we should do with people with disabilities or brokenness is to just throw them away,” says Ventura, who went on to serve as a sherpa for another expedition for a group with disabilities. Her ambition laid the groundwork for future trips, including an ongoing partnership with Waypoint Adventure, an organization that provides outdoor adventure opportunities for people with disabilities.

Two years later, another unconventional group set out: an all-women’s patrol. Eight participants, at least five of whom were over the age of 50 (including Obenschain’s mother-in-law), spent eight days canoeing on the Adirondack ponds. They, too, had the full La Vida experience—ropes course, rock climb, day hike and solo.

Sherpa Pam (Jelliffe) Mulvihill ’85—who co-led the trip with Obenschain’s wife, Katherine—remembers a park ranger stumbling upon the group during his regular rounds. Somewhat befuddled at seeing 50- and 60-year-old women scaling a rock face, she says, “He was amazed that women would do that, would choose to do that.” But as Mulvihill recounted at a recent La Vida “Black Fly” storytelling event, “In the end, most of [the women] loved how the trip stretched and challenged them way beyond their comfort zone. It turned out to be the ultimate commitment move for some of them.”

By year 20, La Vida had a home, a dedicated following and a lot of potential. But it lacked the sophistication it would need to expand further. “When I came back in ’91, I knew we needed to get a property,” recalls Eric Wilder ’85, who was a student when La Vida first came to Gordon and then returned to serve on staff for 14 years.

La Vida had been renting property on Saranac Lake, and Wilder recounts, “The staff would live in MASH tents all summer long . . . the groups would meet in a parking lot, and La Vida would just start.” The infamous celebration dinner of hamburgers and hot dogs at the end of an expedition happened under a tarp in the middle of the woods. “The next morning, you’d get up and start the 10-mile run and head back,” he says. “You didn’t see civilization until you got home . . . Once we got the property, things changed.”

Wilder scoured real estate listings, eventually locating a parcel of land, the former Camp Triangle, just 15 miles down the road from Young Life’s property. He dubbed it “Camp Potential.”

When La Vida acquired that 74-acre property with 15 buildings in Lake Clear, New York, in 1995, it was a turning point. Now there was a true home base—an official starting and ending point, housing for staff, storage for gear, bathrooms and (importantly) a kitchen for the celebration dinner. Capacity and operations increased considerably.

With the base camp property came more responsibility— heightened regulations, licensing from the Department of Health, risk management—all of which Nate Hausman ’00, director of outdoor education, has helped navigate in his 21 years directing expeditions. As a student, Hausman was part of the second trip group to use base camp, which at the time was only partially usable because of trash and animal infestation.

Top on the list of more recent challenges that Hausman has navigated: cell phones. “Now that’s so much of the focus for people,” he says. “Parents want to know, ‘How can I get a hold of them? What happens if something goes wrong? Can they bring their phone with them?’” La Vida holds fast to its principle of unplugging in the wilderness but faces more resistance as reliance on technology grows.

La Vida’s expansion over the second half of its life involved opening a Rock Gym in Gordon’s Bennett Center and an indoor Activity and Training Center at the Brigham Athletic Complex, launching Adventure Camp for middle- and high-school students, and adopting the Compass program for high school students with strong leadership potential (which later launched as its own nonprofit). La Vida donned a fuller name (the La Vida Center for Outdoor Education and Leadership), relocated offices a few times and expanded its staff. It also helped create or replicate its programs in Romania, Ecuador, Kenya, China and South Africa. Participation grew fivefold, now with nearly 5,000 individuals each year experiencing life-changing transformation—and in turn impacting the lives of those around them.

Through the College’s Faith Rising campaign, the next phase of growth for La Vida will open the door to the outdoors a little wider by pursuing even more opportunities to make the wilderness accessible to all. In the summer of 2019, harkening back to its early days, La Vida piloted new partnerships with two Boston-area organizations to again bring urban youth to the wilderness. Sixteen youth spent 10 days in the Adirondacks—many sleeping and cooking outside for the very first time—learning the importance of daily devotionals, perseverance and working as a team to overcome challenges.

Why? To create, as Kielsmeier aptly put it, that “shared meeting ground in the neutral territory of the outdoors”—where survival and success are built not on wealth, status or ability, but on the tenets of community, faith and character.

The Bell

The Bell