Childhood Vows: How Love Gave Alice Tsang the Stamina to Escape Poverty

In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month at Gordon, The Bell interviewed Professor in the Practice of Economics and Business Alice Tsang who has taught at Gordon for over a decade. This is her story.

At midnight, when she was in secondary school, Alice Tsang would climb out of the cramped bottom bunk she shared with her mother and two younger brothers, careful not to wake them or her maternal grandmother on the bunk above. She’d tiptoe to the small common area where, in the wee hours of the morning, she did her schoolwork while everyone else slept—all 15 or so of them.

Throughout her childhood and adolescence, Tsang shared her 350-square-foot Hong Kong apartment with 12 to 16 other people, depending on the year. Her father died when she was five years old, leaving Tsang’s mother with two (soon to be three) mouths to feed and a trail of debts to pay. “My mom proved to be very resilient and resourceful,” says Tsang. Her mother divided their small apartment into rooms and rented them out, creating a meager but stable income for herself in a down economy. “At that time in Hong Kong, jobs were hard to come by and she was often unemployed. On top of that, she had epilepsy.”

Because they shared a bed, Tsang would wake up horrified whenever her mother had a seizure in her sleep. The seizures worried Tsang. Even though her mother never complained about working 84-hour weeks washing dishes in a restaurant or 12-hour shifts carrying building materials on a construction site, Tsang could see the physical and psychological stress her mother was under and vowed, as a young child, to do everything in her power to take care of her. “My goal was to grow up fast and find a good job to support her,” remembers Tsang. “That was my life goal for the longest time.”

Destined to Become a Child Factory Worker in Hong Kong

After elementary school, most of the girls Tsang’s age went to work in the factories full time. Elementary school education was free for everyone, but afterward the cost of a child’s education was determined by how they performed on a standardized test. The brightest went to government-funded public schools and everyone else had to pay for a private education. Of course, most poor families couldn’t afford the tuition and so their children worked instead. However, Tsang qualified for a spot in a public school.

Tuition was free, but school lunches and public transportation to and from school were not. The HK$7.50 Tsang needed each week to continue her education was more than her mother made in a single day, on average. A day’s pay went to food and shelter. There was never any money left over. Fortunately, Tsang’s mother came from a tightknit family. Her brother, sister-in-law and four nieces and nephews all lived in the apartment with them, in addition to her mother (Tsang’s grandmother). And when her brother heard about her dilemma, he offered to cover the costs of Tsang’s school lunches and transportation for all of middle school and high school, even though he did not make much working as a carpenter. “That changed my life,” says Tsang. “A good education was my only ticket out of poverty.”

Giving Up a Comfortable Life as a High School English Teacher

As more opportunities came her way, Tsang’s career aspirations evolved. The girl destined for factory work had dreams of becoming a personal secretary, then a college graduate, a high school English teacher and, years later, a Wall Street bond analyst.

After graduating from the University of Hong Kong, Tsang was hired to teach English full time at an elite high school she would have never gotten into as a student. She thought she’d arrived. “I was about to break into the middle class, and was prepared to spend my life teaching high school English,” says Tsang. “As I later found out, God had other plans for me.” Those plans involved uprooting her comfortable life in Hong Kong and studying in the U.S. to test the advice of a close friend—and see if she really had the chops for a Master of Business Administration degree.

Her friend, who was getting his MBA at the time, thought Tsang would thrive in a program like his. It seemed like an absurd idea to her at first, especially considering that she’d flunked high school math and still had trouble balancing her checkbook. But after a trip to visit him in New York City, she felt inspired to test his theory. She moved to New Jersey to take a few math and accounting classes at a local community college and excelled. “It opened my eyes,” says Tsang. “It showed me those things could be learned.”

From community college, Tsang went to New York University to begin her MBA studies in finance. Once again, she felt tremendous pressure to excel and was living in another kind of poverty. As a graduate student, she could only afford a barely furnished apartment in New Jersey that got so cold during the winter months she’d have to leave the oven door open to keep warm. To pay for living expenses, Tsang earned a little money by sewing for garment factories. Several times a week, she’d make the three-hour roundtrip to the factory, transporting raw materials and finished garments in a collapsible shopping cart she’d take with her on the subway.

The Culture Shock of Being an Asian Woman on Wall Street in the ’80s

Having an MBA and graduating with distinction didn’t protect her from the recession of the early ’80s. Because jobs in finance were hard to get without connections, it took Tsang over a year to land her first full-time job on Wall Street. Eventually she was hired as a junior analyst at E.F. Hutton, the nation’s most profitable brokerage firm at the time. There, she experienced a lot of culture shock. “Women were rare. Asian women were even more rare,” explains Tsang. “There were few minority workers in a prestigious firm like Hutton and I often felt out of place. Not being familiar with American culture, I could not integrate into the daily conversations.” Most of her colleagues were White, male and from affluent families. Around the coffee maker, they’d talk about sports and their Ivy league days. On the weekends, they’d play golf together. Some of them would tease Tsang about her foreign accent. Instead of trying to fit in, Tsang poured her energy into her job. “The culture shock helped me focus on doing good work and serving my clients well. I tried to absorb everything I was learning. I couldn’t get enough.”

From there, Tsang went on to work for Merrill Lynch, Municipal Bond Insurance Association and Fidelity Investments. She even won awards for being the nation’s top water/wastewater utility analyst for two years in a row. Before coming to teach at Gordon, Tsang spent 25 years in the financial sector. She also earned her CFA charter in 1997.

Realizing God Was Behind Every Major Life Opportunity

During those years, Tsang got married, gave birth to a son and finally fulfilled her childhood dream of taking care of her mother. In 1991, she invited her mom to come live with her and her family shortly before her son, Austin, was born. This time her mother had a bed (and a room) all to herself. “My mom had been with us until 2018 when she passed away. She lived a good 30 years or so in much better conditions,” says Tsang. “We are thankful that God enabled us to spend so much time with her.”

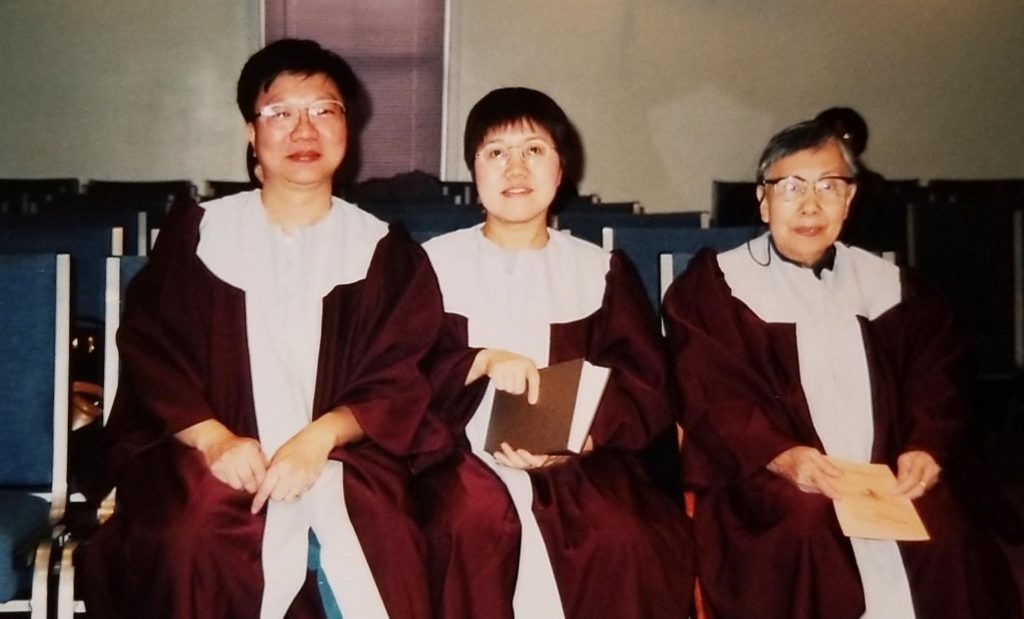

In 1998, Tsang was baptized on the same day as her mother and husband. They’d all made the decision together after attending Sunday services at Austin’s Chinese school, which was housed in a Chinese church.

Before she became a Christian, Tsang had always believed that her deceased father was the one helping her to reach these unbelievable milestones. In Hong Kong, she grew up believing—like many Chinese people—that ancestral spirits watched over her and had influence on her circumstances. “Finally, it dawned on me that it’s not my dead father helping me, but my very much living heavenly Father,” she says. “It took me long enough to answer the call to Christ, but when I did, it just made so much sense. If not for the Lord’s grace and mercy, how could anyone explain what I have become?”

Most, If Not All, Things Can Be Learned

This is why 11 years ago, after retiring from the finance sector, Tsang volunteers her time to teach at Gordon and continues to give generously to the school. “Seeing what I’ve been able to experience, how can I not be grateful to God? That is the reason why I am teaching—I want to share with students my grace-filled journey, and show them how far, with God’s help, they can advance. I am passionate about helping students discover their God-given potential and developing their resourcefulness so they may be blessings to others.”

Tsang says that she comes across many students who are convinced they’re bad at math or unfit for the corporate world. To this, she says, “It’s important we don’t become self-limiting and create roadblocks for ourselves to attaining success. Things can be learned if we invest our time and energy into them.” She points out that we limit ourselves the most, not when we zero in on our past mistakes or the things we don’t know, but when we forget we are Christians. “When we remember we are Christians,” says Tsang, “we can say, ‘If God is for us, who can be against us?’”

The Bell

The Bell