Conversation Leading to Communion: A New Paradigm of Mentorship

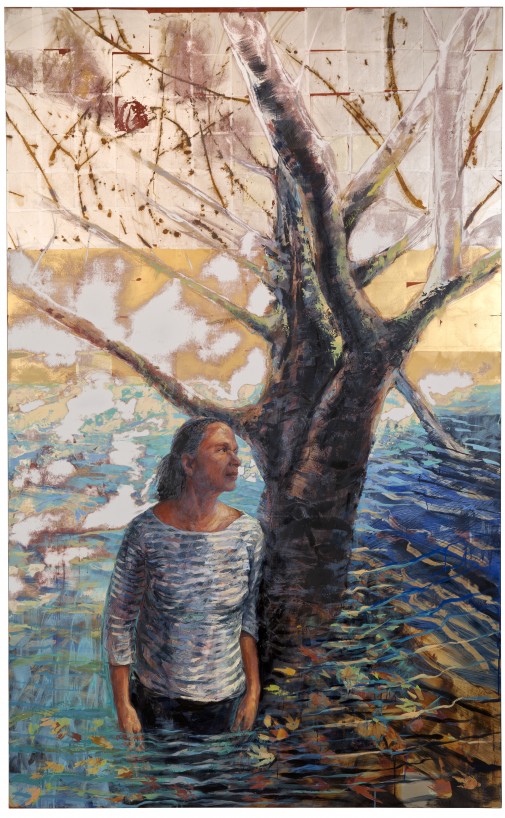

Influential art professor Bruce Herman (pictured above, left) transports you into the sometimes-esoteric art world with a simple, relatable idea: There’s that moment when good conversations with good friends go deeper and deeper as though they are never going to reach the bottom. It expands you and changes you. That, he says, is communion.

It’s a sentiment that Herman shares with fellow painter and mentee Bryn Gillette ’01 (pictured above, right), whose work evidences Herman’s influence. The two artists have “deeply shared values, deeply shared ideas, deeply shared feelings and intuitions and insights,” Herman says.

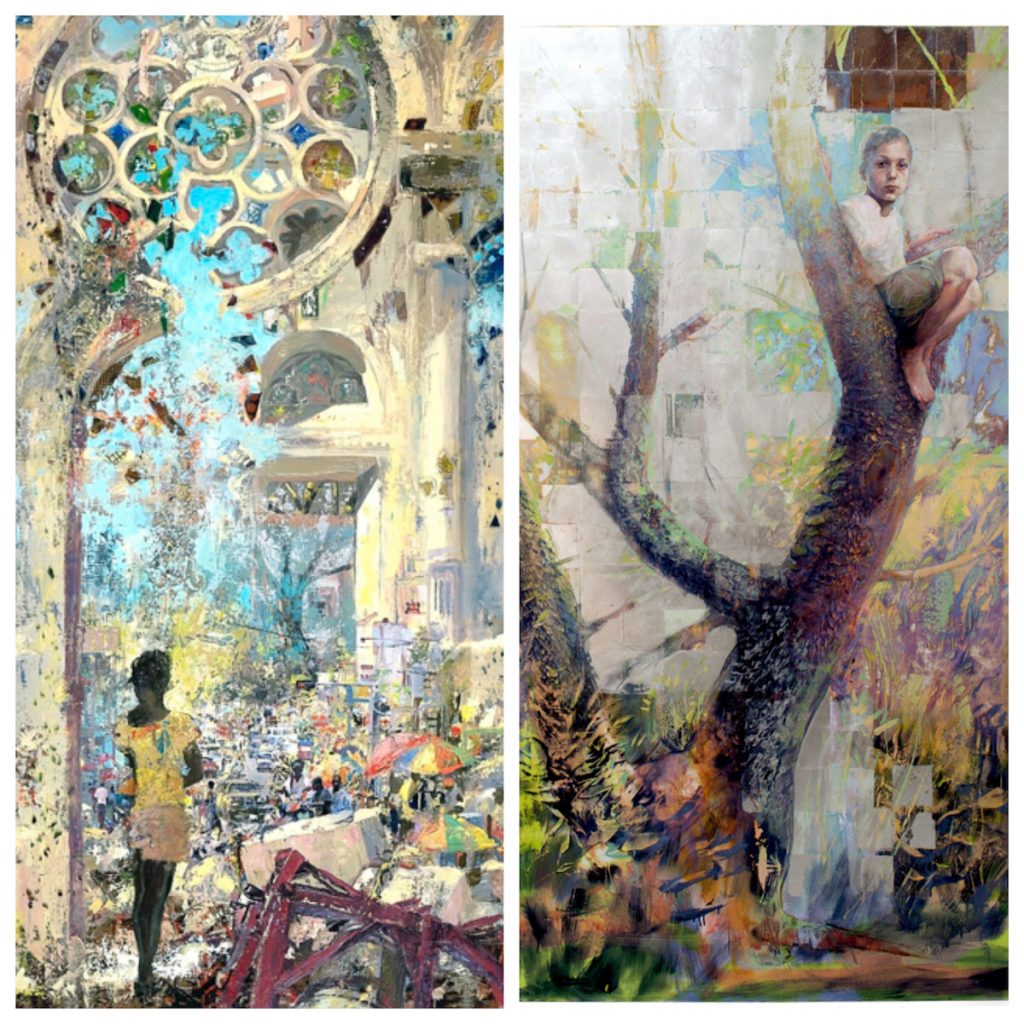

L: “Beyond the Ruins – Cathedral,” oil on door panel, 32×80 by Gillette; R: “QU4RTETS No.1 (Spring),” oil and gold/silver leaf on wood, 97×60 by Herman

Among these is an attunement to the Spirit during the painting process—an element quite distinct from the common culture of their field. “I want to serve the Body (of Christ) as an artist because I believe that my gift is from God,” Herman says. “And a gift isn’t for yourself—it’s for other people. You’re given a gift by God, so you can give it away. For the last 30 years, I’ve been trying to find ways to serve the Body both locally and nationally, and now, these days, internationally.”

Herman’s T.S. Eliot-inspired QU4RTETS series of paintings, created in collaboration with other Christian artists, has been on exhibit in places as distant as Hong Kong. Gillette, too, participates in the international art scene. In August 2016, his commissioned painting, “The Gospel for Every Person,” was unveiled at the Lausanne Movement’s Younger Leaders Gathering in Jakarta, Indonesia. “I found myself praying for the nations as I passed over them with colors,” he says, “thinking of the countless lives, stories and value of people in each region.”

Collaboration, Herman says, “is about getting outside of yourself and your own preoccupations and listening for and building toward common ground with others—kind of the project of meaning-making, essentially. Because you can’t have meaning on your own. If you just have your own idiosyncratic meaning, it’s basically nonsense.”

While Herman is well-recognized among the fine arts circles in academia, Gillette has found his footing as a highly sought-after commissioned artist. His work as a “visual scribe,” documenting occurrences in real-time, takes place primarily at his local church, where he may, for example, capture the essence of a sermon in a painting on stage. “In the act of painting,” Gillette explains, “(I) pray on their behalf to say, “Lord, how do you see them? What is their nature? What’s a word for them and can I document that?”

Before finding his niche, Gillette first had to weave together his artistic gift and pastoral heart. And as a student, he was not convinced the two could work together. “I thought they were exclusive roles—that either you could be an artist or you could be a missionary, or you could be a pastor or you could be a great husband,” Gillette says.

Fortunately, he had what he calls an “echo” of who he was called to become in his mentor, Herman. “He is, in his own life, a great artist and a great pastor and shepherd, and a great husband and a great father. So, he really modeled for me the balance that life could hold,” Gillette says.

Today, Gillette spends his days teaching art at an all-boys preparatory high school, learning the “nuts and bolts of teaching well,” he says. It is here that the Herman protégé finds himself in a similar role as his mentor. “I’m hoping that I’m modeling for them that kind of future man and husband and father and professional that they could emulate,” Gillette concludes.

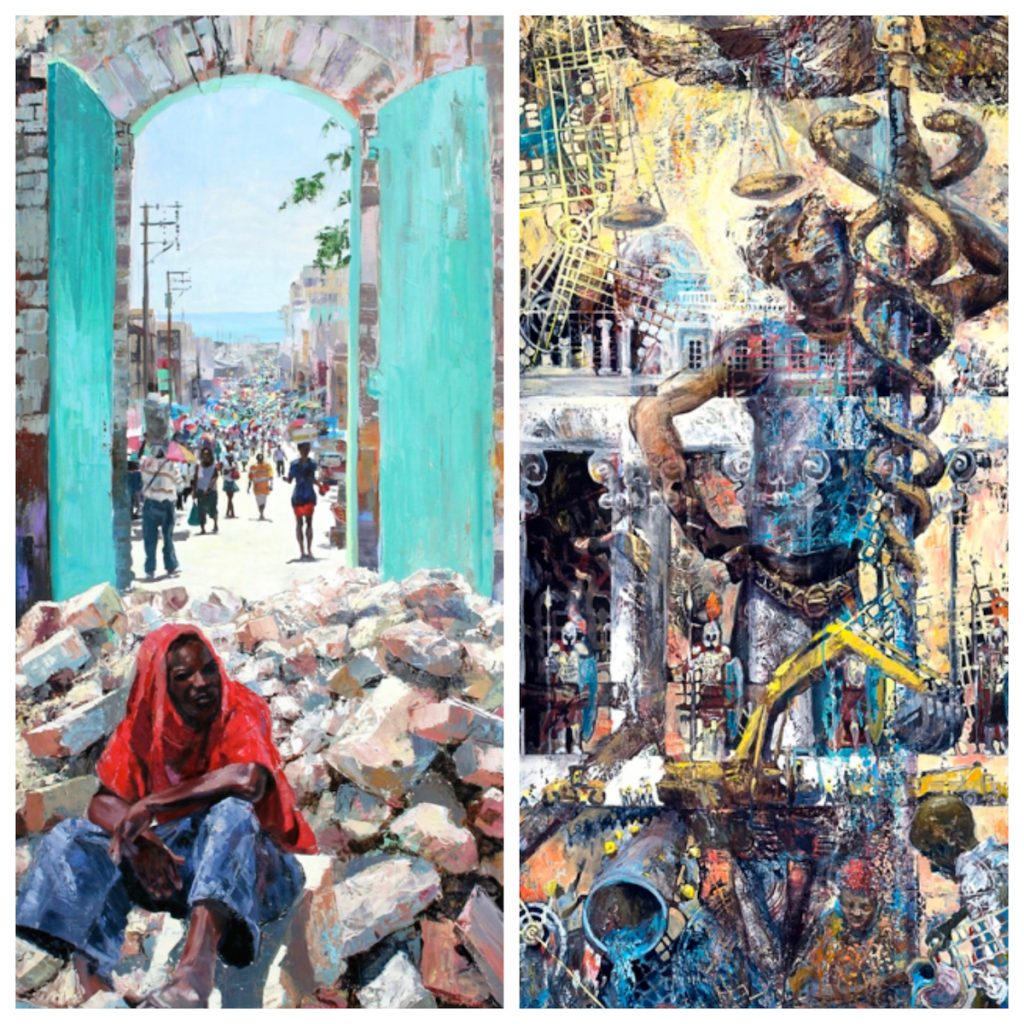

That distinctly Christian vision comes through in Gillette’s “Beyond the Ruins” series. Informed by a transformative friendship with a Haitian orphan-turned-pastor, Gillette expresses what it would look like for the Kingdom to come down to a place such as Port-au-Prince, which suffered a cataclysmic earthquake in 2010.

L: “Beyond the Ruins – Green Doors,” oil on door panel, 32×80 by Gillette; R: “Beyond the Ruins – Government 2,” oil on door panel, 32×80 by Gillette

“(Bryn is) now one of the artists that I know (who is) really connecting art and social justice, caring for others, building up the body of love,” Herman says. “It’s funny because so much of our heart is the same,” Gillette says of Herman. “I don’t know where the end of me (is) and (where) he begins.”

By Dan Simonds ’17, communication arts

The Bell

The Bell