Gordon Archives (Re)discovers Ancient Cuneiform Tablets

Deep behind the glass display cases of a museum you’ll find rows and rows, shelves upon shelves of objects often never seen by visitors. Packed away behind the scenes—something akin to the Ark of the Covenant getting stored away amid endless crates at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark—museums house treasures that simply cannot fit in the limited display space.

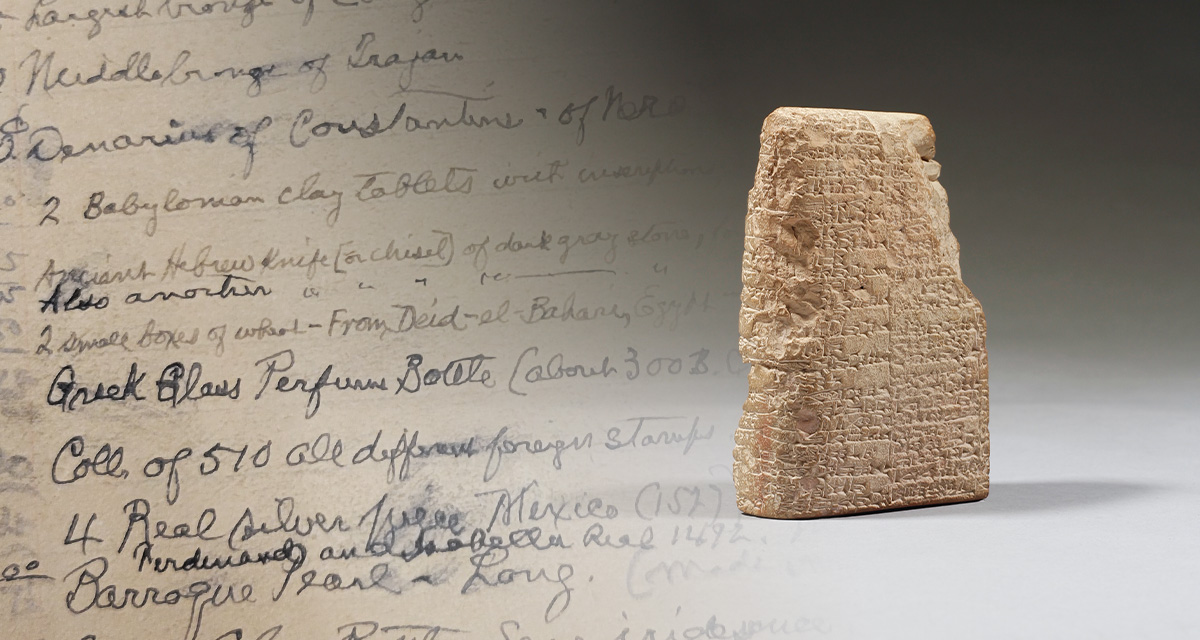

During the Gordon Archives’ ongoing campaign to organize the maze of artifacts in the Vining Rare Book Collection with a modern cataloging system, Jenks Library Circulation Manager Sarah (Larlee) St. Germain ’17 and her team of student workers made a discovery lying within: Two clay tablets featuring engraved cuneiform script, possibly dating back between 2070 and 1658 B.C.

An unexpected (re)discovery

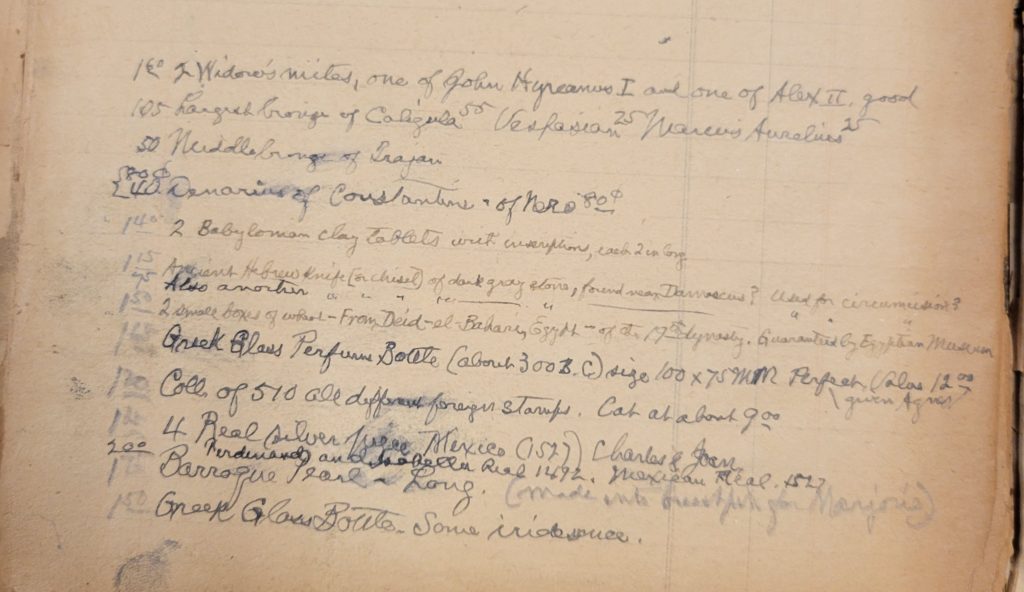

One day last semester while intern Drake Sprowles ’24 was comparing inventories and catalogs against what was on the Archives’ shelves, he stumbled upon a note that said, “clay tablet.” St. Germain recalls, “He looked at me and said, ‘Do you think this is really a clay tablet?’” They walked to the back of the Vining stacks where the call number was listed. Looking inside the silver archival box, St. Germain found two plastic sandwich bags wrapped in Styrofoam padding. Inside the simple sandwich bags were two tablets.

“We were laughing at the impossibility of what we had rediscovered and the absurdity that these possibly ancient tablets were just sitting in sandwich bags,” says St. Germain. “We were on cloud nine.”

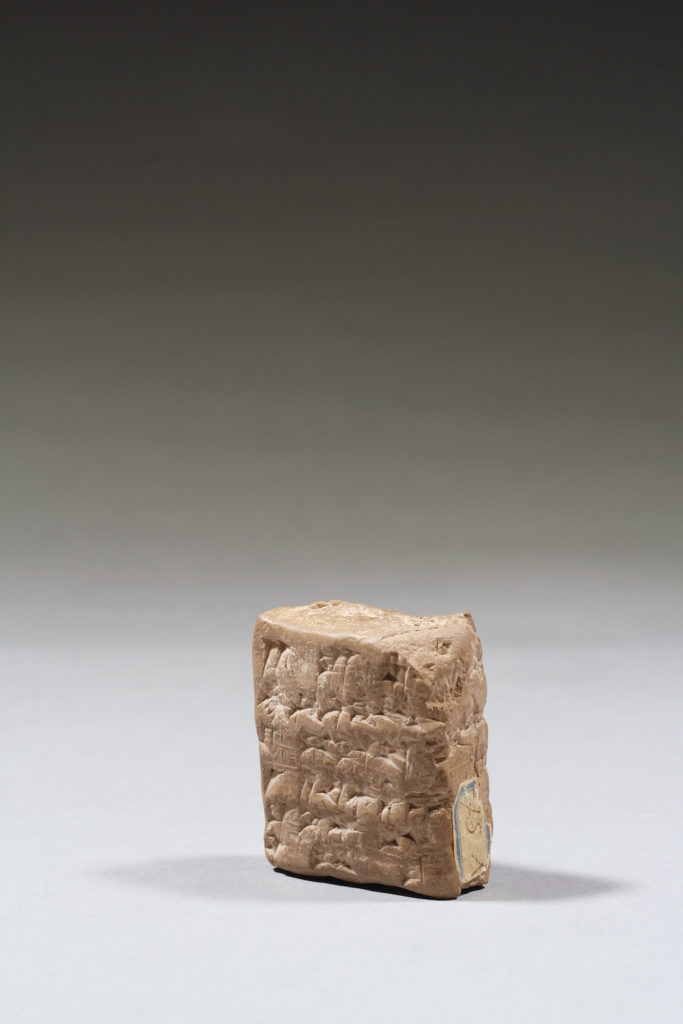

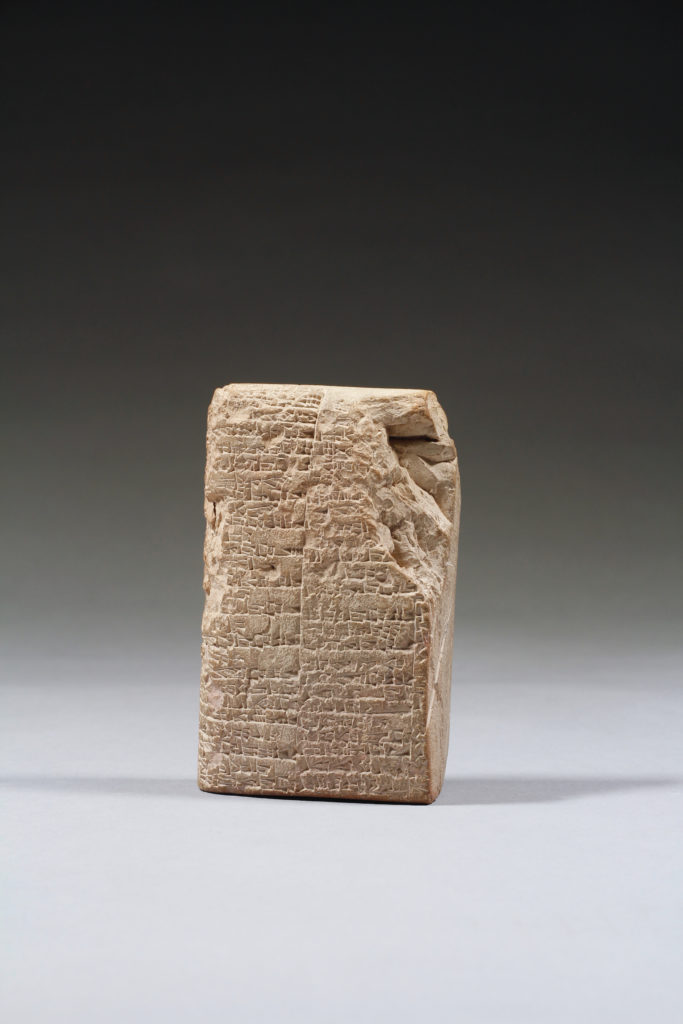

The two tablets belong to the Vining Rare Book Collection, the personal library of collector Edward Payson Vining, donated to Gordon College, then named the Gordon College of Theology and Missions, in 1921. Item descriptions enclosed with the tablets, perhaps packed away in the Gordon Archives after they were gifted, label one as a cuneiform tablet from the First Dynasty of Babylon, dated to 1658 B.C., possibly a record of a loan. The other is identified as a legal document from the Third Dynasty of Ur, dated 2070 to 1960 B.C., possibly an inventory tablet recording payments of commodities to a temple. If these dates are correct, the tablets are Gordon’s own rare examples of tablet usage predating Moses and the Ten Commandments at Sinai.

How could these ancient artifacts remain “hidden” for so long? “There was no indication on the box about the materials within being tablets,” St. Germain explains. When she and Sprowles realized the potential significance of the unlikely find, they began calling faculty who teach languages, linguistics, ancient history and biblical studies and others involved with the Gordon Archives to see for themselves.

“The fact that we have something this old is incredible,” says St. Germain. “You’d see them in places like the Museum of Fine Arts or Harvard or Yale, but to see them at a small Christian liberal arts college is mind boggling.”

St. Germain says the discovery further invigorates her efforts to promote the Gordon Archives’ collections and share its rich contents with campus. “Having these types of materials at Gordon makes history come alive,” she says, highlighting the benefits of interacting with artifacts in person instead of looking at photos in a flat book. She points to tablets’ three-dimensionality, revealing how no clay was left unused. “They wrote on the front and back and all the edges,” she observes.

Mysteries in the details

Despite the thrill of the discovery, St. Germain resisted the urge to instantly throw the tablets into a glass case and host an exhibit grand opening. First, she needed to confront some discrepancies and solve mysteries behind her rediscovery. Examining the full contents of the archival box, St. Germain and her interns found an additional note suggesting errors:

“. . . the year 1658 B.C. puts the tablet not in the first dynasty but in the Kassite dynasty. Furthermore, the name Samuiluna is not found in the king lists of either dynasty. There is a Samsu-iluna in the first dynasty, who reigned from 2080 to 2014 B.C.”

St. Germain says a couple of theories could explain the potential misdating—Vining himself may have purchased the tablets with incorrect information, or he may have hired someone who dated them incorrectly. An error may also have been introduced at some point while in the College’s possession. And the discrepancy between “Samuiluna” and “Samsu-iluna” could even be as easily explained as “an old-school typo,” says St. Germain.

“Are they incredible finds? Absolutely,” says St. Germain. But she wants to do thorough research to rule out those possibilities. “I feel very strongly about my responsibility to get the right information on the tablets.”

A mission to crack the code

To ensure the Gordon Archives have as full a picture as possible for future students and researches, St. Germain is recruiting input from Dr. Gordon Hugenberger, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary senior professor of Old Testament, and ancient Middle Eastern languages and civilizations expert Dr. William “Bill” Barker ’98, who will become president of Southern Wesleyan University this summer.

Hugenberger says translating cuneiform tablets is a patient, precise—and potentially pricey—process. Experiencing the small tablets in person, says St. Germain, a viewer can understand why it is difficult to read, transcribe and translate cuneiform. According to Hugenberger, many experts are using computers to crack the codes with special lighting techniques. He explained to St. Germain in an email:

“This problem is why it is estimated that out of some one million or more cuneiform tablets that have been discovered (which is more texts than exist for Latin!) and are now housed in museums or university and college libraries around the world, over half of these texts have still not been transcribed, much less transliterated, translated or studied.”

Because scientific methods of dating the tablets are major investment of time and funding, she says “It’s possible that we may never have a clear identification.” But she remains determined to learn as much as possible, explore more options and advocate for opportunities over the coming years. “It’s certainly a process,” she says, “but one I think will ultimately result in a semi-answer.”

The Bell

The Bell