Picking Tori’s Brain: Lessons from a Chemist, Climate Activist and Convalescent

In April, the University of Colorado suspended all non-essential research and Tori Arau’s lab was appropriated for a new purpose: to measure air quality during the coronavirus shutdown. With her own research on cloud formation on hold, she helped a team of atmospheric chemists set up their scientific instruments.

Their results did prove that we were breathing cleaner air than before, but it wasn’t time to celebrate. Arau ’19, who was in the middle of her first semester of graduate school at the time, explains that the shutdown made a small dent in a very big problem. “One hundred companies cause 70 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions,” says Arau, quoting the Carbon Majors Report.

You can’t stop global warming with a two-month pause in industrial and human activity. And some would say you can’t stop the coronavirus with a six-foot rule.

“One of the professors at my school, Jose Jiménez, studies aerosols,” says Arau. “COVID can travel in the aerosol droplets we produce when we talk. [Jimenez] is currently arguing that the six-foot rule isn’t enough and that we should be thinking of it in terms of a 25-foot rule. This is hotly contested by most people, if only because they don’t want to behave with a 25-foot rule.”

Right now, epidemiologists find themselves in a similar situation to climate change scientists, where they’re faced with responses of skepticism and doubt. “Climate change scientists are saying to the epidemiologists, ‘I understand what you’re feeling because people ask me if it’s real, too.’ People question if the data is true because it means things are going to change.” says Arau.

Although Arau is someone who understands the data as an atmospheric chemist, she knows that change, on a personal level, is hard. “I don’t like change either,” says Arau. “If anything, the last year has taught me that I really don’t like change, but I also know how to deal with it when the time comes to change.”

When it Came Time for Arau to Change

Just under a year ago, before Arau began what was supposed to be her first semester of graduate school, a car slammed into her driver’s door as she was making a left turn. She and her car escaped visible harm, but the impact left her with a traumatic brain injury and eight rotated vertebrae.

In the weeks following the accident, she became borderline non-verbal, wore red-tinted glasses everywhere to keep migraines at bay, slept 16 hours a day and wrote things like “Have you eaten today?” or “Have you brushed your teeth?” on sticky notes around her apartment. “My brain forgot what it was like to have a routine,” says Arau.

She deferred her first semester of graduate school, and with one semester under her belt, she’s now deferring again for the same reason. “I’ve just finalized paperwork to take a leave of absence from school, which is bittersweet,” says Arau. “I know it’s what I need to be doing to support my long-term wellbeing, but it’s also hard to again, even if temporarily, relinquish something that has been a long-term goal. [My memory] is better than it was, but it’s also not where it needs to be to be a functioning scientist.”

Change Disrupts Order

At 22, Arau knows that if she wants to get back on a bike this summer she’ll need training wheels. “But going to buy training wheels feels wrong,” Arau admits. “Most 22-year-olds aren’t relearning how to ride a bike.”

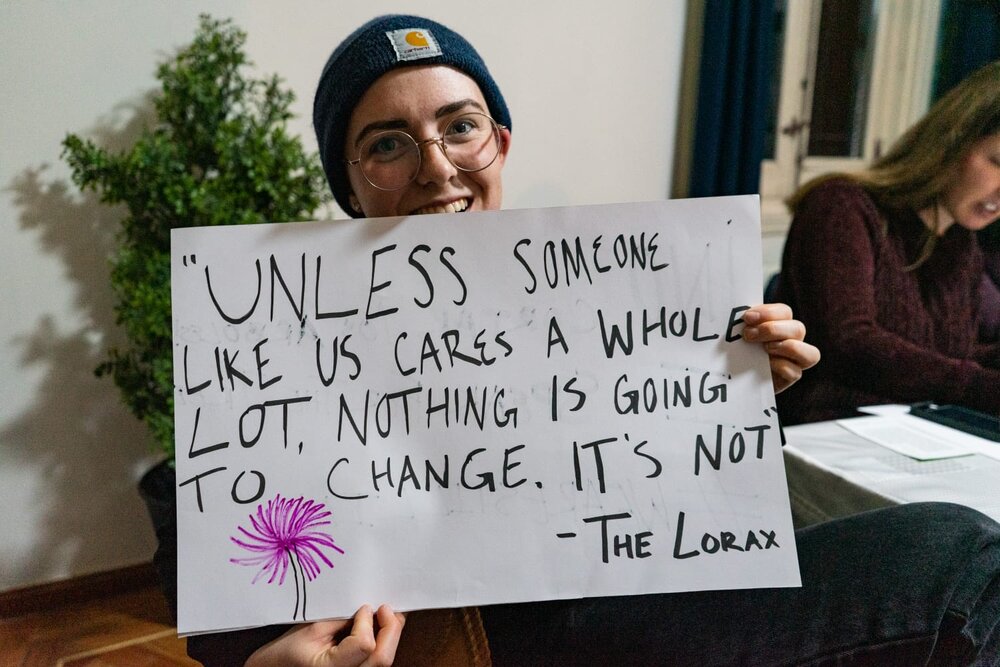

And yet, Arau’s injury afforded her an opportunity to do something else ahead of schedule. With a little nudge from former professor and friend Dr. Dorothy Boorse (biology) by way of a Facebook post, Arau applied for a spot in the Christian Climate Observers Program (CCOP) and, last December, she attended the Climate Talks in Madrid hosted by the United Nations (pictured above). Being there gave her a window into how the world’s government goes about finalizing an international response to climate change.

“Going to one of the UN Climate Talks has long been on my bucket list,” says Arau. “I wouldn’t wish a traumatic brain injury on anyone; [but] it gave me the space to go to the UN meeting. It’s not to say it’s been easy, but the right opportunities have always come along.”

You Can’t Put a Timeline on a Healing Brain, a Planet or a Human Population

As much as she’d like to, Arau says, “you can’t really put a timeline on healing a brain.” The same can be said for healing the planet or ending a pandemic. Even though she won’t able to predict how this will all turn out, she still finds the courage to listen to the data even if it means she will have to change.

Arau says, “It does not feel great to be rewriting the plan . . . I don’t expect that I won’t feel that twinge of heartbreak when the semester starts in the fall and I am distinctly not there. But I know, pending my brain’s needs during this time, it’s necessary to be able to do what I want to in the long-term. Even though I don’t like how powerless I feel, God knows what’s coming and it will work out, even if I don’t feel like it will.”

The Bell

The Bell