Six Black Heroes and Heroines of Gordon’s Past

In honor of Black History Month, The Bell retells the stories of six Black men and women—all graduates of Gordon and Barrington—who went to great lengths to shift the currents of history. During the Great Depression, they provided a safe haven and network of support for Black believers during a time when the Black population was unemployed at nearly twice the rate of the general population. In WWII, they liberated the people of Europe and the Pacific as part of a segregated military—which is to say they fought for the freedom of others when they didn’t yet have it themselves. Another brought traditional African religiosity back into the fold of Christianity after years of misunderstanding and demonization. And others brought education, medical care, affordable housing and the gospel to the poorest regions of Haiti. They each, in their own way, inspire us in the present to be brave, truthful and kind.

Here’s a small window into the remarkable lives they led:

Robert and Carol (Crews) Dokes ’30

Robert and Carol Dokes were ministers, teachers and civil rights activists who devoted their lives to Christian service and racial justice. Together, they cofounded Second Baptist Church in Paterson, NJ, which provided a safe, communal space for fellow African Americans to share their testimonies and life experiences. It was a community they poured into for 44 years. Outside the church, Robert and Carol taught adult literacy classes during the bleakest years of the Great Depression, as part of an initiative run by the Works Progress Administration.

During WWII, Robert joined the U.S. Army and served as a chaplain, first lieutenant and captain for several segregated, all-Black military units, including the famous Harlem Hellfighters.

Back then, the army didn’t hire enough Black chaplains, so Robert was responsible for serving the spiritual needs of roughly 1,200 men, which meant he did the work of nearly four White chaplains. It was a great burden, especially considering how much his love and care was needed in an environment where racial discrimination was ingrained. Robert tried to protect his men by serving as a buffer and intermediary between his Black soldiers and the White officers.

Robert fought back against the racism he encountered by doing everything he could to equip his soldiers for positions of leadership. In addition to being their chaplain, he was also their teacher. In a letter to his wife, Robert explained that he taught his soldiers “a little English and spelling each Monday evening to aid them in qualifying for the Officer Candidate School” (Dokes to CC. Dokes, March 25, 1943). And it worked. In another letter to his wife, Robert shared, “Sgt. Pollard is now a Warrant officer and eats at the officer’s mess. He worked hard and replaced an officer of the opposite group. We may get another colored Warrant officer before long.”

In 2020, Gordon named its new accelerated pastoral degree program after Robert and Carol. Learn more about the Dokes Ministry Scholars.

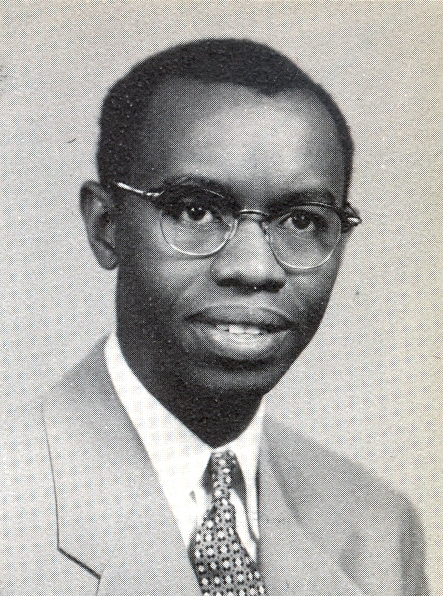

Rev. Dr. Arthur L. Whitaker ’49

Whitaker was a WWII veteran, Baptist pastor and renowned sociologist who devoted his life to the work of racial justice during the Civil Rights Movement and the decades that followed. He was also a personal friend of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The two met as divinity students in Boston in 1952.

Whitaker’s famous sociological analysis of the 1964 Rochester race riot helped the nation understand that the only way to prevent future riots and improve race relations was to fix the problems that drove people to riot in the first place—problems like overcrowding in Black neighborhoods, a segregated public school system and police brutality against Black residents. In “Anatomy of a Riot,” he wrote, “The ‘why’ of any catastrophe is never easy to answer . . . Violence is nurtured in an atmosphere of unrelieved frustration, resentment and despair. Violence does not provide the answer nor can it be condoned . . . But last summer’s riots in Rochester, New York; Philadelphia; and elsewhere were rooted in the social and economic disadvantages foisted upon the Negro by an apathetic, if not insensitive, society.”

His words earned a place in the Congressional Record and eventually inspired U.S. Congressman and government officials to investigate racial discrimination within the American military and make Martin Luther King Jr. Day a legal holiday in the state of New York, paving the way for King’s birthday to become a national holiday. For more on Whitaker, check out “The Redemptive Side of Anger.”

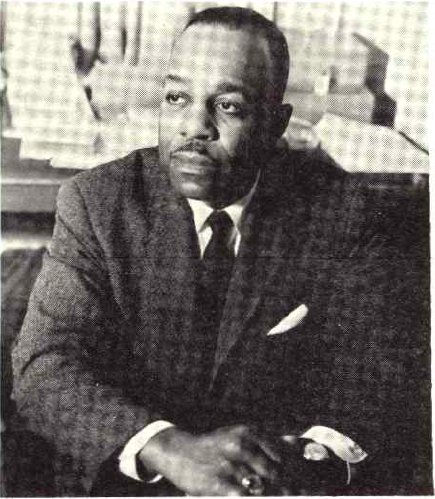

John Mbiti ’57B

Mbiti was an Anglican priest, university professor and the father of modern African theology. He was the first Christian philosopher to see the beauty, depth and truth in traditional African religions that had been dismissed and demonized by imperialists and missionaries. He wrote the first book on African religiosity—apart from two small works written by English missionaries—titled African Religions and Philosophy, which was published in 1969. His words changed the way people understood God’s revelation to humankind. He wrote, “God is not insensitive to the history of peoples other than Israel. Their history has a theological meaning.”

Mbiti saw—through his studies of traditional African religions—how God was present in places untouched by Christianity. Before the missionaries came to the African continent, Africans already worshipped a God who was omnipotent, omnipresent and eternal. In an article he wrote for the Christian Century, he explained, “The missionaries who introduced the gospel to Africa in the past 200 years did not bring God to our continent. Instead, God brought them. They proclaimed the name of Jesus Christ. But they used the names of the God who was and is already known by African peoples—such as Mungu, Mulungu, Katonda, Ngai, Olodumare, Asis, Ruwa, Ruhanga, Jok, Modimo, Unkulunkulu and thousands more. These were not empty names. They were names of one and the same God, the creator of the world, the father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Christian Century, August 27–September 3, 1980, pp. 817-820).

As part of Homecoming 2021, Mbiti will receive the A. J. Gordon Missionary Award posthumously, so stay tuned for more information on Mbiti’s incredible legacy.

Lydie ’58B and Jean Claude (Clyde) ’57B Noel

The Noels met at Barrington College (which later merged with Gordon in the 80s). They were both international students from Haiti. Upon graduation, they moved to Port au Prince where Clyde began his work for the Evangelical Association of Haitian Churches. Lydie would often accompany him to his downtown office. When she did, Clyde said, “She started seeing the women in the streets . . . with babies in their hands, begging and others trying to find jobs.” It didn’t take long before Lydie “started inviting these people in the streets to come into our office,” said Clyde (Partners with Haiti, “Lydie’s Vision—AFCA Village,” YouTube video, 0:55–1:38, January 20, 2018).

From then on, it became her mission to feed them, start schools for their children and build a neighborhood that would give them access to affordable housing. So in 1981, Clyde founded Partners with Haiti, the umbrella organization for all of their ministries. Together, they built churches, schools, medical and dental clinics, homes, an orphanage and a vocational center. For 60 years, they worked hard to meet the most pressing needs of those living in underserved regions of Haiti. And today their legacy lives on through their countless ministries and the school feeding program that provides nutritious meals to nearly 500 children every weekday—so that hunger doesn’t interfere with a student’s ability to learn and study.

Check out www.gordon.edu/blackhistorymonth for a list of upcoming campus events and weekly African Proverbs from Mbiti’s personal collection.

The Bell

The Bell