Complicated Miracles: Life in Paradise a Year After the Camp Fire

A version of this article, featuring Katherine Sorich ’05 and four other Gordon alumni, appears in the fall 2019 issue of STILLPOINT magazine under the title “Good Samaritans in the Burn Zone.”

Through almost every window in her house, Katherine Sorich ’05 can see hard hats loading melted debris into dump trucks. Debris that used to belong to her neighbors whose empty lots are now sectioned off with yellow caution tape. Apart from the old man who comes by from time to time on his ATV, the Soriches are the only ones on this stretch of Paradise.

Last year in November, the Camp Fire hit Sorich’s hometown like a tidal wave, displacing 52,000 people and laying waste to 14,000 residences, but her house wasn’t one of them.

Then it felt appropriate to use the m-word. Miracle. When Sorich returned to Paradise for the first time after a harrowing escape from the fire, hardly anything remained. Her mountain town in the Sierra Nevada foothills, once lush with lofty California oaks, was now an apocalyptic landscape where brick chimneys stood up out of the rubble like gravestones.

The Camp Fire had burned up the staircase eight feet from Sorich’s front door along with the two sheds behind the house. It had damaged everything within a 20-foot radius, and came close enough to the house to make the paint bubble. So, why then would it suddenly turn around?

Dangerous ripple effects

After being back in Paradise for five months, it’s getting harder for Sorich and her husband to see their situation as miraculous. Their miracle landed them back in a ghost town that’s not really safe or comfortable for anyone.

“You might say we’re stuck with a house up here,” says Sorich. “People feel like we’re the lucky ones, but we are sort of feeling left behind. It’s hard waiting for Paradise to be built up again.”

The schools they were planning to send their three children to have burned down. The soil in their neighborhood is being tested for asbestos. And the jury is still out as to whether the water is safe to drink. State officials have tested the water lines and have identified which parts of town are free of benzene, a chemical that puts people at risk for developing blood cancers like leukemia. But, scientists and engineers are saying that the testing protocols are not stringent enough—and that Paradise residents don’t have enough information to know if their water is harmless or not.

Paradise has become a place where exposing yourself to dangerous chemicals is as easy as taking a breath. Toxic dust, full of contaminates that were once tucked safely away under kitchen sinks and on garage shelves, can kicked up into the air by a gust of wind, a passing dump truck or a pair of hazmat workers moving debris.

The hard work of healing

Sorich and her husband, Scott, are grateful to have a home, but it’s hard for them not to imagine what life would have been like if they had been forced to move elsewhere—where their kids could play in the park and go to a good school, where they could enjoy the company of their neighbors, where they wouldn’t have to worry about breathing in heavy metals during a walk to the mailbox.

But wishful thinking hasn’t kept them from playing an active role in their hometown’s recovery. They’ve been in this since day one, since the moment Scott put on his Butte County deputy sheriff uniform and got the cross-traffic moving on a deadlocked side street, saving hundreds of people from burning up in their cars.

It’s possible none of that would have happened had Sorich not been on that deadlocked side street, two toddlers in tow, and informed Scott that she and everyone else on Nunneley Rd. were stuck.

It started with helping people escape Paradise, and now it’s helping them to return.

Their church, Paradise Evangelical Free Church (PEFC), is one of three that are still convening in Paradise, and the Soriches are a part of a core group of 35 people who are committed to the church’s new vision.

“We’re treating it like a church plant with lots of community outreach,” says Sorich.

In recent months, PEFC has retrofitted their church building to accommodate 50-plus volunteers on a daily basis. That includes a commercial kitchen (still in progress), a shower building and 48 new bunks beds. Currently, they are one of two churches in Butte County that are housing and feeding Camp Fire recovery volunteers. In partnership with PEFC, volunteers can build tiny houses for Camp Fire survivors who cannot afford to rebuild their former homes, assist the Butte County Fire Safety Council with removing brush and debris, distribute clean water and survey new residents to help determine arising needs.

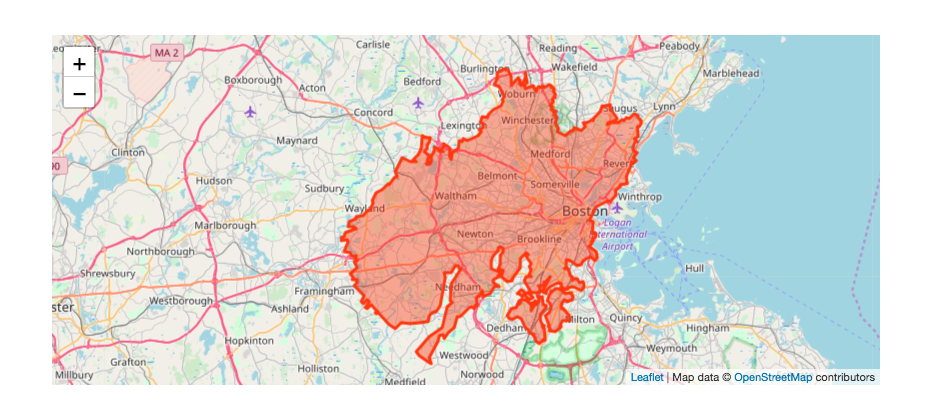

If the Camp Fire had taken place in Boston, the burn zone would cover this area. Interactive map courtesy of NBC News, the U.S. Geological Survey, and OpenStreetMap contributors.

While the reminders of the Camp Fire are still everywhere—in the water, in the soil and in the air—with each passing month they fade a little. They get further away. Before, it only took Sorich eight steps from her front door to step on something that had been charred by the fire. Now, it takes 20.

“That’s life here almost a year later,” says Sorich.

Like other complicated miracles, such as the parting of the Red Sea, there is a lengthy period of wandering that follows. Although the people of Paradise are not wandering in a physical sense, they are waiting for their lives to feel normal again. With enough help, it won’t take 40 years.

For those who are interested, there are a few ways to take part in Paradise’s recovery. If you’d like to volunteer or bring a service team to the burn zone, you can reach out to Chad Fransen ’94, Chico-area pastor and member of the Camp Fire Long-term Recovery Group, at [email protected]. For those who cannot make a trip out to Paradise, you can still give financially to the Camp Fire Pastors Response Team.

Header image courtesy of Lori Eckhart. Mural by Shane Grammer.

The Bell

The Bell