Healing Post-Soviet Ukraine through Music

When Yo-Yo Ma—perhaps the world’s most famous living classical musician—played his cello at the border entry point in Laredo, Texas, last April, it was a perfect example of how the culture of classical music is changing. Every year, more and more classical musicians are leaving red-curtained concert halls for unconventional venues like local aquariums, hospitals, airports, libraries, even national parks.

Just before the start of the fall semester, 11 of Gordon’s string chamber musicians and two faculty flew 4,400 miles to add another uncommon venue to that list: a remote, Soviet-era orphanage for men and boys with intellectual disabilities. Not only had this audience never heard live music before, they had never left the orphanage grounds.

The first song they heard live was a movement of Dvořák’s American Quartet, performed by Gordon’s ensemble. Later, the men and boys in the audience played along to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy with hand chimes. “We made music with them,” says Dr. Sarita Kwok (music). “It just fed their souls and it fed the souls of the people who were working in that orphanage.”

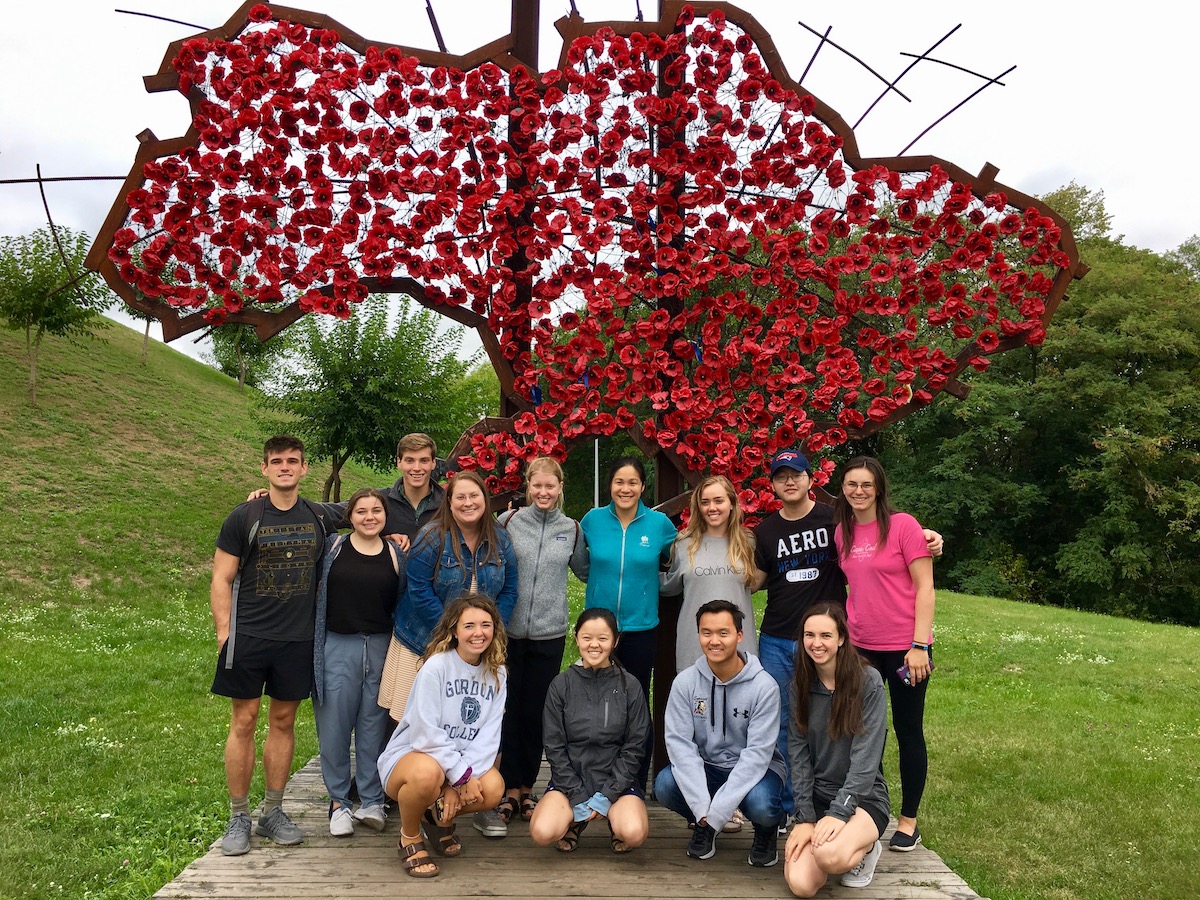

Before heading to the orphanage in Romaniv, the group visited the Motherland Monument in Kyiv, Ukraine. Pictured from left to right, in the back row: John Macgregor ’19, Sarah Zahorodni ’19, David Bergeron ’20, Dr. Jessica Modaff, Sophie Wood ’21, Dr. Sarita Kwok, Abigail O’Grady ’20, TaeIn Kim ’21, Rachel O’Connor ’20. In the front row: Katelyn Lashley ’22, Anna Bailey ’21, Matthew Rhee ’22 and Leanne O’Connor ’22

This was the first time Gordon organized a mission trip with a music focus. Several of these Gordon string majors had performed internationally, in places like Seoul and Hong Kong, thanks to music tours funded by a generous, anonymous donor. But this was the first time they traveled somewhere to, as Kwok describes, “be on mission in the world through music.”

Kwok brought her chamber music class to Ukraine because she wanted her students to understand how music, like medicine or evangelism, is capable of transforming someone’s life—or even an entire culture—in a very short amount of time. After a day at the orphanage in Romaniv, the group headed to Zhytomyr to spend six days volunteering with Music Camp International—a music camp for 150 middle-school students, disabled and non-disabled alike.

Through Music Camp International and other like-minded organizations, music is accomplishing something extraordinary in Ukraine. It’s empowering a nation of people to break away from the harmful teachings and practices that were instilled during the communist era and reign of the Soviet regime. One hundred years ago, the government told parents it was in their best interest to turn their disabled children and impoverished children over to the state, and that’s still happening. Government-run orphanages, like the one in Romaniv, are not unusual. There is a whole population of children and adults out there who’ve never heard music before—who’ve never seen past the walls of their bedroom.

But in bringing music to children and adults inside and outside the Ukrainian orphanage system, musicians are changing how Ukrainian youth perceive themselves. In the simple act of teaching a child to play a song on the xylophone, a person can restore dignity, confidence and hope to a child that has been cast aside or told they possess no talent.

In a documentary about Music Camp International, founder Connie Fortunato elaborates, “I’ve seen children who are shy become confident. I’ve seen children who were told they weren’t talented realize that they were. A lot of children with down syndrome and autism spend their entire life in one room and we put them on a stage. They sing and they smile.”

The trip has given the group of Gordon musicians a lot to think about. “This experience really showed me how music is a universal language,” says violinist Rachel O’Connor ’20. “You don’t have to speak Ukrainian to teach a child from Ukraine how to play the violin. We placed their fingers on the strings. We showed them how to do it.”

This ability to read body language and other nonverbals is a trait of a chamber music musician, explains Kwok. Chamber music originated in, well, a chamber. It began with a group of musicians that could all fit in one room. Because they didn’t have a conductor, they had to learn to read each other’s body language.

“Chamber music is a very intimate form of music-making. You learn a lot of intuition. You learn how to change roles,” explains Kwok. “Sometimes you’re the melody. Sometimes you’re harmony. Sometimes you’re the bassline. In all of these roles, you have a different task and you have to be flexible enough to move between the roles.”

Gordon’s ensemble performed a concert for children and families in the main cathedral of Zhytomyr, which was featured on a Ukrainian television special. Pictured from left to right: John MacGregor ’19, Anna Bailey ’21, Sophie Wood ’21 and Rachel O’Connor ’20

The trip to Ukraine offered Kwok’s students a way to use this kind of intuition in the real world. Without words, they were able to teach each Ukrainian student to play two instruments—to learn an entire song well enough to perform it in front of an audience.

“To be able to take those skills and transfer them into a mission setting in another country with a different language has been very powerful,” says Kwok. “It was life-shaping for our students to be in the presence of Connie Fortunato—someone who has impacted the lives of over 50,000 children through music.”

But Gordon’s relationship with Connie Fortunato and Music Camp International is just beginning. This upcoming May and June, the Department of Music will launch an international internship called “Teaching Music for Social Transformation,” which will give up to eight music majors the opportunity to intern with Music Camp International in both Ukraine and Romania, and earn college credit. The hope is to continue this internship program well into the future.

After all, true healing doesn’t take place overnight or even in the course of one week at music camp, especially when a nation of people had been under the thumb of communism for nearly 100 years. So, Gordon will continue to send more musicians over the next few years, to continue the work of healing in Ukraine through music.

The Bell

The Bell