What Does Art Have to Do with the Cross?

If you were to acquire a time machine and attend an ancient Mediterranean dinner party, your host might present you with half of a tessera hospitalis—a small tile symbolizing hospitality and welcome, broken in half, part for the host and part for you. In that gesture, Lothlórien Distinguished Chair in the Fine Arts and Barrington Gallery Director Bruce Herman sees a moment of theological vulnerability and the source of artistic communion.

“We were invited by grace to God’s table, [where] Christ himself is the symbol that is broken: ‘Here’s my body broken for you,’” says Herman. “He invites us across the threshold, into his dwelling to sit at his table. His hospitality is the ultimate hospitality and all art flows from that.”

Last week for the Center for Faith and Inquiry (CFI) Arts Lecture, Herman shared how art can point us to God. Here are some of his insights:

Studying the fine arts changes your life. “Something’s transformed in your imagination and your intellect [and] your heart,” says Herman. “This is where knowledge becomes wisdom, because to follow Christ is the ultimate wisdom that this world has to offer.”

Like faith, art requires vulnerability. “You cannot encounter [a] work of art unless you’re willing to submit to it,” says Herman. “You cannot really experience the fullness . . . unless you’re willing to let down your guard . . . But of course, there’s a cost. There’s a risk: you might be changed by it. And you might be changed in a way that you don’t want to be changed.”

Play reveals the heart of God. Every morning at 6:30 a.m., Herman’s grandson comes downstairs and sits on his lap. Soon, he’s ready for a creative activity, like building a cardboard robot (or two) with a multitude of colorful buttons. “He always wants to make something,” says Herman. “That spirit of play is at the heart of God. It is not just a childish thing; it’s the heart of creativity.”

Goodness is not always “pretty.” In contrast to the sweet moments with a child, consider the explosive violence of a supernova, the power of the Colorado River carving the Grand Canyon or a hurricane seen from space. “It’s absolutely stunning, but it’s also incredibly powerful and scary,” says Herman. He identifies a perhaps archetypal example in Psalm 50:3: “Our God comes and will not be silent; a fire devours before him, and around him a tempest rages.” And yet, says Herman, “in the same sentence we hear about the perfection of beauty.”

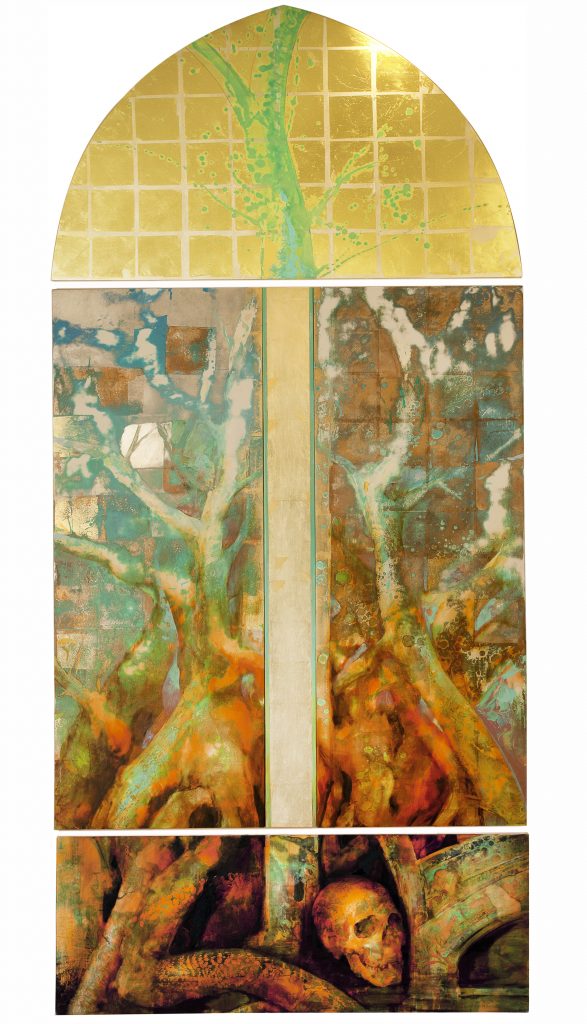

Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is a picture of goodness. That perfect beauty can lead to sacrifice, says Herman—in the case of Christ, it was “the ultimate good of the cross . . . That is the true picture of good, and yet it’s a conflicted picture,” he says. “The cross is a terrible thing just as that supernova is a terrible thing, but also a beautiful thing causing us to leave our comfort zone and hold up our part of the symbol.”

The Bell

The Bell